Tourniquet Pain after Ultrasound-Guided Axillary Blockade-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Journal of Anesthesia

Abstract

Objective: To analyse tourniquet pain after

ultrasound guided axillary block (AXB) as the sole anesthetic technique

with no injection of local anaesthetic into the subcutaneous tissue of

the posterior half of the axilla to prevent tourniquet pain.

Material/patients and methods: 84 patients

older than 18 years ASA I-IV undergoing surgery at hand, wrist, forearm

and elbow under ultrasound guided AXB requiring upper arm tourniquet, we

studied prospectively. Exclusion criteria included refusal to

participate, communication problems, pre-existing neuropathy,

coagulopathy or allergy to local anaesthetics. Tourniquet pain was

assessed according to visual analogue scale (VAS) every 15 minutes. We

also analysed differences in tourniquet pain between sedated and

non-sedated patients.

Main results: VAS was 0 during ischemia in 83

patients. One patient reported tourniquet pain. This was mild (VAS = 3)

and reported during the first 15 minutes of ischemia. VAS dropped to 0

from then on. The median ischemia time was 62 minutes (IQR 45-86) and

the median surgery time was 60 minutes (IQR 40-89.5). Intraoperative

sedation was administered to 48.8% of patients. Sedated and non-sedated

groups were similar. No statistical differences were found regarding

tourniquet pain between both groups (p< 0.05).

Conclusion: Ultrasound guided AXB is

sufficient to provide anaesthesia for tourniquet even during prolonged

ischemia. However, to ensure prevention of tourniquet discomfort a

multiple injection technique that include musculocutaneous blockade

should be preferred.

Keywords: Tourniquet pain; Axillary block; Ultrasound-guided peripheral nerve block; Upper limb surgery; Sedation

Background

Regional anaesthesia holds potential advantages when

compared to general anaesthesia. Particularly, brachial plexus blockade

has demonstrated superior analgesia, reduction of opioid-related side

effects and opioid consumption during the first 24 hours after surgery [1]. The axillary blockade (AXB) provides anaesthesia for upper extremity surgery of the elbow, forearm, wrist, and hand [2,3]. It has been shown as effective as supraclavicular (SCB) and infraclavicular (ICB) blocks [4] but its distal location from pleura and phrenic nerve eliminates some of the risks related to those more proximal approaches [5,6].

Ultrasound guidance allows direct observation of

nerves, surrounding structures and local anaesthetic (LA) spread. Its

use decreases complications and onset time [7,8], improves quality [8] and reduces the volume of LA required [9].

Due to the superficial location of the brachial plexus in the axilla,

ultrasound guided AXB provides excellent visibility of both nerves and

needle.

The intercostobrachial nerve (T2) is not part of the

brachial plexus. It communicates with the medial brachial cutaneous

nerve (C8-T1) providing innervation to the skin of the axilla and the

medial and posterior aspect of the arm. The block of these nerves to

prevent tourniquet pain is widely extended and has been traditionally

recommended using an injection of LA into the subcutaneous tissue of the

posterior half of the axilla ("semicircular subcutaneous anaesthesia"

or "ring block") [1014]. However, its importance in reducing tourniquet pain has never been established and is questioned [2,15,16].

The aim of this study was to assess tourniquet pain after ultrasound

guided AXB as the sole anaesthetic technique. Due to the fact that

intraoperative sedation could underestimate tourniquet pain, further

analyses comparing tourniquet pain in sedated and nonsedated patients

were also carried out.

Material and Methods

A prospective observational study of tourniquet pain

on patients who received an ultrasound guided AXB was conducted over a

four month period (January- May 2013) at Galdakao- Usansolo Hospital.

The study was classified as service evaluation and no ethical approval

was needed as required no alteration to the routine standard of care,

there was no therapeutic or equipment intervention, and no planned

change to anaesthetic technique. Written consent from patients was

obtained. Inclusion criteria were patients undergoing surgery at or

below the elbow under ultrasound guided AXB requiring upper arm

tourniquet, age >18 years and ASA (American Society of

Anaesthesiologists) status I-IV. Exclusion criteria were refusal to be

included, communication problems or inability to cooperate, pre-existing

neuropathy, coagulopathy or allergy to LA.

After patient arrival to theatre an intravenous

catheter was placed in the upper limb contralateral to the surgical site

and ASA standard monitoring were applied. Ultrasound guided AXB were

performed by either consultants with expertise in regional anaesthesia

or residents supervised by those consultant. A portable ultrasound

machine (Sonosite M-Turbo®) and high frequency linear probe was used.

Administration of premedication or intraoperative sedation was left to

the discretion of the treating anaesthesiologist. The ultrasound probe

was applied in the axilla to obtain a short-axis view of the axillary

artery. The four terminal nerves (median, ulnar, radial and

musculocutaneous nerve) were sought out and their identity confirmed by

scanning distally along the arm following the characteristic course that

each nerve takes. A 22 gauge needle (Braun Stimuplex D) was used to

surround each individual nerve with LA after skin infiltration with

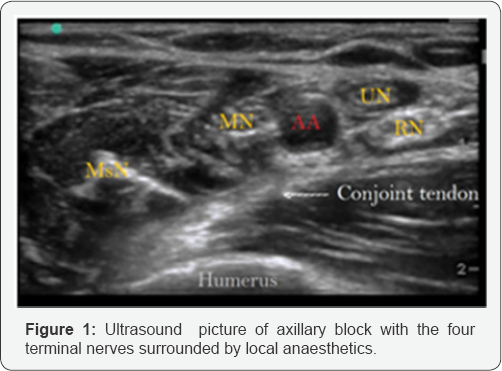

lidocaine 1% (Figure 1).

The AXB approach (in plane or out of plane) and the type and amount of

LA was decided by the anaesthetist who performed the block.

AA: Axillary Artery; RN: Radial Nerve; UN: Ulnar

Nerve; MN: Median Nerve; MsN: Musculocutaneous nerve; Conjoint tendon of

the latissimus dorsi and teres major

Once the block was finished, a pneumatic tourniquet

was applied to all patients on the mid-upper arm over a single wrap of

cotton wool padding. The limb was exsanguinated using an Esmarch bandage

and the tourniquet cuff inflated between 250- 300mmHg.

The variables collected included age, gender, weigh,

ASA status, type of surgery, premedication administered, type and amount

of local anaesthetic used to surround each nerve, time between the end

of the block and the tourniquet inflation, pressure of the tourniquet,

ischemia and surgery time, intraoperative sedation and tourniquet pain.

The primary objective was to analyse tourniquet pain assessed according

to a 0-10cm visual analogue scale (VAS), whereby '0' represents no pain

and '10' represents the worst imaginable pain. Tourniquet pain was

measured directly after the tourniquet was inflated and thereafter every

15 minutes (min) until the tourniquet was deflated. VAS evaluations

were conducted by the same person who performed the block. As a second

objective we analysed differences in tourniquet pain between

intraoperative sedated and non-sedated patients.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis of socio-demographic and

clinical variables was made by using frequencies and percentages for

categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous

variables. The exception being variables with a high level of deviation.

These were represented by median and interquartile range. The

differences between sedated and non-sedated patient were evaluated using

the Chi-square test (or Fisher exact test when expected values<5)

for categorical variables and non-parametric Wilcoxon test for

continuous variables. All effects were considered significant at

p<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS for Windows

statistical software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Carey, NC).

Results

Over the four month period 84 patients were recruited.Patient characteristics and type of surgery are summarized in Table 1.

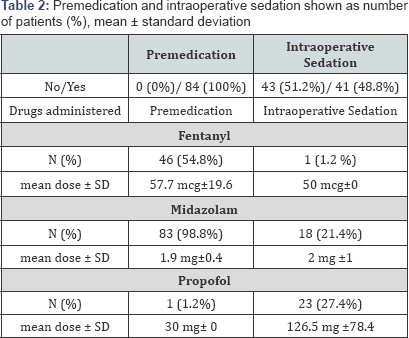

All patients received premedication prior to the block. Intraoperative

sedation was administered to 48.8% of patients. Sedatives used to sedate

patients during surgery were propofol and midazolam but one patient

received 50 mcg of fentanyl (Table 2).

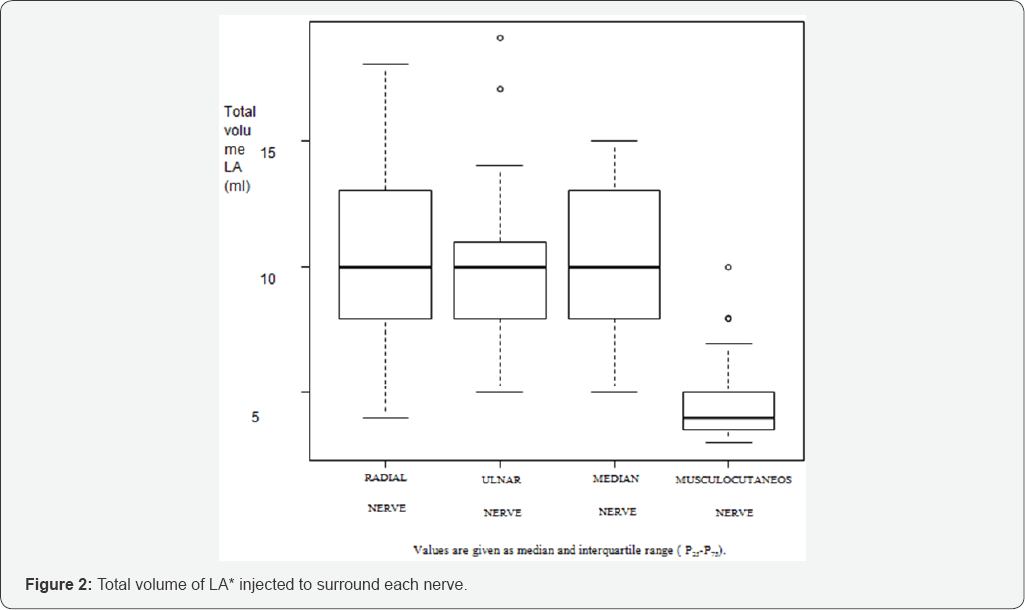

Mepivacaine 1.5% were the LA of choice to surround the four nerves in

all patients. Occasionally Ropivacaine 0.2% or Levobupicaine 0.25% were

added to provide longer analgesia. The mean total volume of LA used was

34.37±5.37 ml (Figure 2).

The median time since the block was finished until

the cuff was inflated was 10min (IQR 5-15). The median surgery time was

60 min (IQR 40-89.5) and the median ischemia time was 62min (IQR 45-86) (Table 3).

Among 84 patients included, 83 scored tourniquet pain

as VAS = 0cm during the time tourniquet was inflated. One of these

patients complained about pain in the surgery field without pain on the

tourniquet site after 180min of surgery and had to undergo general

anaesthesia. In this case, a 30min reperfusion period was used after

135min of ischemia and the total ischemia time with the patient awake

was 150 min. One patient reported tourniquet pain. In this patient VAS

was 3 cm when the cuff was inflated and in the following 15 minutes. He

was administered 50mg of fentanyl and 20mg of propofol respectively.

Since then VAS reminded 0cm until the tourniquet was deflated 31 minutes

later. No more sedatives were administered.

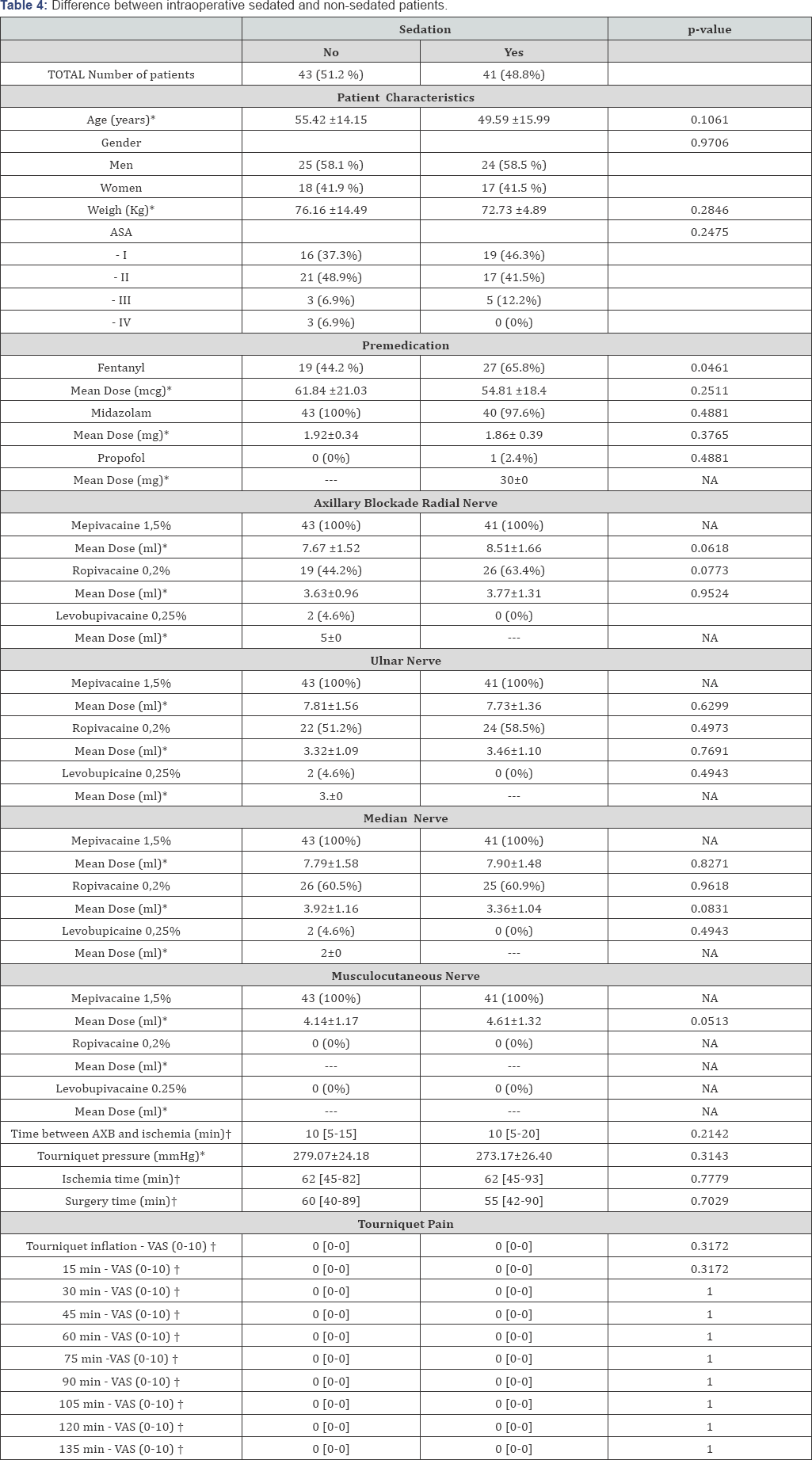

Sedated and non-sedated groups were similar in

demographic variables, ASA status, premedication administrated, type of

surgery, type and amount of LA used, time of ischemia and surgery and

tourniquet pressure. No statistical differences (p< 0.05) were found

regarding tourniquet pain between both groups (Table 4).

ASA: American Society of Anaesthesiologists; AXB: Axillary Block; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale;

Results shown as number of patients (%). *mean ±

standard deviation (SD). †Median [Interquartile range = p25-p75]. NA =

Not applicable. --- = Unknown.

Discussion

Tourniquets are commonly used in upper limb

procedures to improve visualisation, reduce bleeding and expedite

surgical procedures. Despite its advantages, tourniquet might associate

injury that usually involves nerve or other soft tissues and is often

complicated by the development of tourniquet pain [17].

Contrary to the old belief that a dermal component represents one of

the major causes of tourniquet-related pain, ischemia and compression

have been identified as the main sources of noxious stimuli during the

maintenance of tourniquet inflation [18-21].

Due to these findings, there is progressively more belief that during

AXB a tourniquet is well tolerable without requiring additional dermal

anaesthesia [15,16]. Similarly, popliteal blockade is sufficient for tourniquet on the caff with no need of femoral or saphenous block [22]. It is important to highlight the importance of achieving a "complete" AXB [23]. Pain associated to tourniquet has been showed to be significantly reduced when a multiple injection AXB technique is used [24]. S. Sia et al. [25]

comparing a triple injection AXB technique (blockade of median,

musculocutaneous and radial nerves) and a "selective" approach in which

only the nerves involved in surgery were blocked, reported a significant

increase of patient requesting intraoperative administration of

fentanyl for tourniquet pain in the "selective" group.

Despite the numerous anatomical variations of the

four main nerves at the axilla, median, ulnar and radial nerves they all

lie very close to the axillary artery [25].

Due to this proximity, the injection of a determinate amount of LA to

block one of them could cause blockage of the others. By contrast,

musculocutaneous nerve lies far lateral to the axillary artery, in the

fascial plane between biceps brachii and coracobrachialis muscle. It

innervates the muscles in the anterior compartment of the arm - the

coracobrachialis, biceps brachii and the brachialis. To achieve its

block the needle has to be redirected but its blockade is essential to

prevent tourniquet pain [26].

We identified the four nerves by scanning distally along the arm and

observing the nerve tracing. They were surrounded by LA independently.

Among 84 patients, 83 reported "no pain" [27].

Only one patient complained about tourniquet discomfort (VAS= 3cm)

during the first 15 minutes but VAS dropped to 0 cm from then on. This

is more likely to be attributed to a block in progress than to a real

need of additional blocks. Time between block finished and cuff

inflation was just 3 min in this patient whereas, Tran DQ, et al. [28] concluded that the mean onset time is 18.9 minutes when using 4 injections AXB and lidocaine 1.5% with epinephrine 5mcg/ml.

The use of sedation in regional anaesthesia has been

shown to increase patient satisfaction and can also modify pain

perception [28,29]. However, there were no differences in tourniquet pain between intraoperative sedated and nonsedated patients in our study.

Tourniquet pain has been related to the duration of inflation [18]. Five of our patients had ischemia for more than 120min but none of them complained about tourniquet pain. JP Estebe et al. [30],

reported a tourniquet pain tolerance of approximately 2030 minutes in

volunteers. Tolerance was defined in that study when VAS was > 6cm or

when volunteers decided their pain tolerance limit was reached. In

daily practice, letting patients reach either points is unacceptable.

Patients on the operating table suffering a painful experience could

lead to anxiety, patient movement and unsuccessful surgery. Therefore if

a tourniquet is required for surgery, associated pain should always be

prevented and treated.

Fitzgibbons PG et al. [31]

carried out a review regarding safe tourniquet use recommended

tourniquet pressure of 250mmHg for less than 150min in the upper

extremity. We used tourniquet pressure slightly higher and only one

patient exceeded a total ischemia time of 150min, however a reperfusion

time was used on this patient. Although higher pressures and longer

ischemia times than the ones recommended have not demonstrated increased

complication [32],

tourniquet-related injury resulting from excessive tourniquet inflation

pressure or prolonged ischemic time were not an objective of our study

and were not followed up. Some of the limitations of this study included

a relatively small number of patients, observational methodology and

nonrandomized design. Test of sensory and motor blockade were not

recorded, but no incomplete blocks were reported. No blinded observer

data was collected. Ultrasound guided AXB alone provides enough

anaesthesia to cover tourniquet-related pain even during prolonged

ischemia. Use of additional dermal blocks are not required, however a

multiple injection AXB technique that ensures musculocutaneous blockade

should be performed.

For more articles in Journal of Anesthesia

& Intensive Care Medicine please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/jaicm/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/jaicm/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment