Quality Indicators to Assess the End-of-Life Care in the Intensive Care Unit-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Journal of Anesthesia

Abstract

Objectives: Intensive Care Units (ICU) in Hong

Kong incorporated palliative care in the daily practice. We would like

to evaluate the quality of end-of-life care (EoLC) in the ICU.

Design, setting and participants: Quality

indicators consist of 4 domains and 12 indicators were devised. The four

domains were early identification of dying patients; communication and

information; end-of-life care to the patient and care after death. Next,

we applied these indicators to assess the EoLC of patients who died in a

20-beds mixed ICU from 1st Jul to 30th Sep 2012.

Main outcome measures: The 12 EoL quality indicators

Results: Out of the 38 patient records, 33

were included for analysis. There were no objective criteria to identify

dying patients. All the studied families received an EoL

physician-family conference. Although high documentation rate (90.9%) of

the treatment plan and resuscitation status; only 3.0% of the family

conferences addressed the psychological, social and religious needs. No

written information was used. Medication was prescribed in 46.7% for

symptom control and life-sustaining treatments (LST) were withheld and

withdrawn in 90.9% and 45.5%, respectively. In indicated patients, only

66.6% had the process reviewed. Lastly, care after death was

acknowledged in 48.4%.

Conclusion: These 12 EoL quality indicators

were specific designed for ICU patients and easy to implement. Areas for

improvement included early identification of dying patients; training

on assessment of the social, psychological and religious needs of the

patient's family; distribution of information leaflets; assessment and

management of symptoms; and regular review of the process.

Keywords: End-of-life issues; Intensive care; EoLC Abbreviations: VHA: Veterans Health Administration; LCP: Liverpool Care Pathway; EoL: End of Life; LST: Life-Sustaining Treatment

Introduction

End-of-life care is an integral part of care in ICU

especially when treatments fail to accomplish the original goal of

treatment. Uncertainty of disease prognostication was one of the

challenges in EoLC in ICU, and the decision was usually based on the

number of organ failures or selected diagnosis like global cerebral

ischemia after cardiac arrest [1,2].

As most critically ill patients were either sedated or unconscious, the

decision making process invariably involved the patient's family.

Symptom assessment and management in ventilated and sedated patients

posed another challenge of EoLC in the ICU. In order not to unduly

prolong the dying process, withholding or withdrawal of life-sustaining

treatment (LST) usually preceded the death of patients in ICU and it

varied from 0-70% [1,3,4].

In Hong Kong, the EoLC was provided by the ICU team who incorporated

palliative care in the daily practice. In order to evaluate the quality

of the care provided to the dying patients in the ICU, we search for

quality indicators used for this particular group of patients.

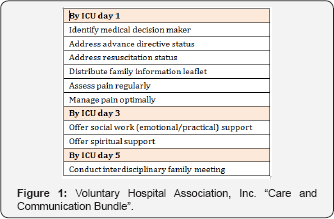

In United States (US), "Care and Communication

Bundle" proposed by Veterans Health Administration (VHA) had been used

to assess the quality of EoLC in the ICU [2,5]. In this bundle, they used Day of ICU admission as the trigger for initiation of end-of-life discussion (Figure 1). However, this practice might not suit our local setting. In Unit Kingdom (UK), the Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP) [6]

had served as the main mechanism to ensure quality of EoLC, especially

in the last days of life. The LCP had 3 key sessions (initial

assessment, ongoing assessment and care after death) and 4 key domains

of care (Physical, psychological, social and spiritual). As LCP had

attracted a lot of criticism, the Independent Review Panel recommended

its use be abandoned [7].

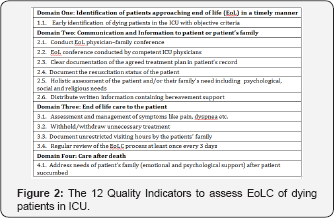

By referring to the quality indicators used from these two countries,

we try to devise a quality tool comprising of 4 domains, namely

Domain One: Identification of the patients approaching end-of-life in timely manner

Domain Two: Communication and information to patient or patient's family

Domain Three: End-of-life care to the patient

Domain Four: Care after death

Under these 4 domains, there were total of 12 indicators as shown in Figure 2. We then applied these 12 indicators to assess the EoLC in a group of dying patients in the ICU.

Method

Prior Ethics Committee approval was obtained to

retrieve the records of patients who died in ICU from 1st Jul to 30th

Sep 2012. End of life (EoL) physician-family conference was defined as

the family interview in which the ICU doctor brought up the issue of

comfort care with the patient's family and the signing of the hospital

DNAR (Do Not Attempt Resuscitation) form. Patients excluded from the

analysis were those who had no close relatives identified; those

families who refused the end-of-life care and patients with unexpected

deterioration in the ICU.

The other data collected include the demographic

data, the APACHE II and IV score, the SOFA score at the time of the EoL

decision, the time from ICU admission to the decision of EoLC, and the

time from activation of EoLC to the death of the patients.

We used these 12 indicators to assess the quality of

EoLC in the ICU. Descriptive statistics were used when appropriate. The

results were expressed as percentages. The denominator was all the ICU

patients with EoLC in the ICU and the numerator refers to the episodes

that fulfilled the criteria.

Result

A total of 38 patients died in the ICU and 5 were

excluded from analysis. Three patients had unanticipated deterioration;

one patient had no close relatives in Hong Kong and one family requested

active treatment until the patient succumbed.

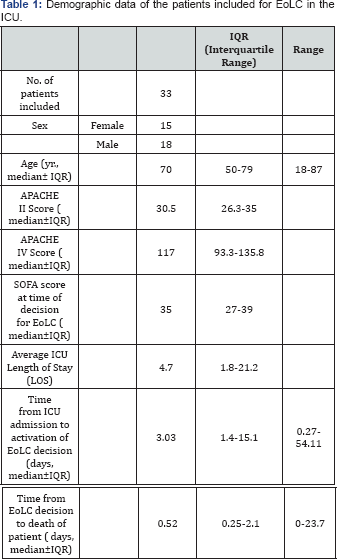

The demographic, APACHE II and IV score of the 33 patients were shown in Table 1.

The median SOFA score at the time of the decision for EoLC was 35

(IQR=27-39); signifying the patients had high probability of dying at

time of decision.

There were no objective criteria for early

identification of patients approaching end-of-life. The median time from

ICU admission to decision of EoLC was 3.0 days (IQR = 1.4-15.1). The

median time from decision of the EoL to death of patient was short and

variable (median of 0.52 days, range from 0 to 23.7 days). Although EoL

physician-family interviews were provided to the family of the dying

patients in the ICU, 84.8% were conducted by an ICU specialist or higher

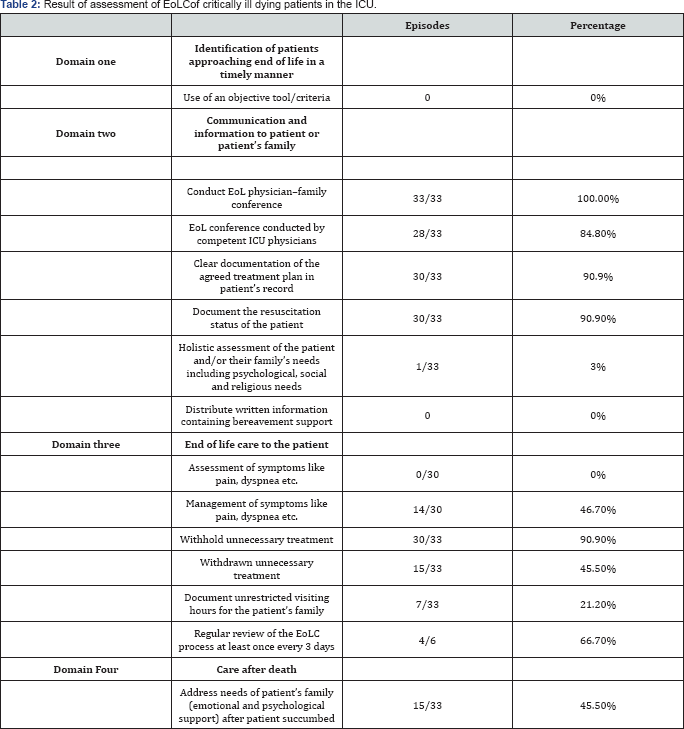

ICU trainees. There was high rate (90.9%) of documentation of the

treatment plan and resuscitation status of the patients (Table2).

For management of symptoms, 3 patients were excluded

because of severe brain injury. Out of 30 patients, 14 (46.7%) were

prescribed medication for symptom control. There was no formal

assessment of symptoms. Treatment were withheld in 90% of patients had

and less than half (45.5%) had treatment withdrawn. Among the patients

with treatment withdrawn, 5 had ventilator support decreased; 5 had

inotrope decreased; 8 had stopped dialysis support and 6 had unnecessary

medications stopped. Six patients survived more than 3 days after

initiation of the EoLC; 4 of them (66.7%) had the process reviewed again

(Table 2).

As for the patients' families; the areas that were

least assessed were the psychological, social and religious needs of the

patients’ families. We did not have any written information to provide

to the patients' families to explain the meaning of end- of-life care.

Although unrestricted visiting hours were allowed for the family, this

was recorded in the documentation in 7 out of 33 EoL records. After the

patient succumbed, the hospital had its own policy on last offices and

handling of the deceased’s body. However, the needs of the patient's

family was acknowledged in less than half of the cases (45.5%) (Table 2).

Discussion

Between the "Consultative Model" and the "Integrated Model" of palliative care service provision in the ICU [2],

most Hong Kong ICUs have adopted the latter model. In a study by Yap et

al, almost all ICU doctors in Hong Kong would apply the

"Do-Not-Resuscitate" order; 99% and 89% of them would withhold or

withdraw therapy in dying patients, respectively [8]. In general,

limitation of therapy was applied when we were quite confident that the

patient would die or had no chance of meaningful recovery. In order to

evaluate the EoLC in the ICU, we need to identify the quality indicators

that reflect the whole process of care; from identification of dying

patients to care after death. Indeed, implementation of palliative care

quality measures had been regarded as one of the most promising

strategies to improve EoLC service [5].

In the UK before 2014, the Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP) [6] had served as the main mechanism to ensure quality of EoLC, especially in the last days of life [9]. However, there were limited experiences of using the LCP for EoLC in the critically ill patient [10]

. For indicators that were specific to ICU, the Robert Wood Johnson

Foundation Critical Care End-of-life Peer Workgroup proposed the use of

seven domains and 53 quality indicators [11].

To facilitate the use of these indicators in daily practice, the

Veterans Health Administration (VHA) developed the "Care and

Communication Bundle" and narrow down to nine measures [2]. In contrast to most ICU in US,ICU admission in Hong Kong was limited by bed availability [1,8].

Hence, the use ICU stay Days 1, 3 and 5, as the trigger for EoLC might

not be applicable to us. With some modification, we chose 4 basic

domains and 12 indicators to assess the quality of EoLC in our local

settings.

The importance of the "diagnosis of dying" has been brought up by the recent independent review of the LCP and another study [7,9,12].

In Buckley's study, instead of listing the objective criteria to

identify the dying patients in the ICU, they retrospectively reported

the reasons for initiating a discussion on limitation of therapy with

the family [1].

In Buckley study, the mean time from ICU admission to the EoLC decision

was 7.8 +/- 13 days. In our study, the median time for ICU admission to

the decision for activation of EoLC was 3 days (IQR=1.4-15.1 days).

Both studies shown a wide variation in the timing of bringing up the EoL

discussion. The inherited uncertainty in disease trajectories and

prognostication of non-malignant disease [13]

has made the identification of triggering factors rather difficult in

critical illness. Although there were reported triggering criteria for

activation of palliative care consultation [2,14], there were no

unifying objective criteria for early identification of dying patients

among critically ill patients. This may lead to wide variation in the

decision to activate EoLC.

After the implementation of the Care and

Communication Bundle in ICUs in the US, the overall reported pain

assessment and management in three ICUs had improved to 76% and 81%

respectively [15].

In this current study, all the patients were intubated, rendering the

assessment of pain and other symptoms more difficult. In 46.7% of

indicated patients, medications were prescribed for symptom relief.

Assessment of symptoms was important as some patients (e.g. those with

severe brain injury) might not need medication for pain relief while

those who needed them might not have the medication prescribed to meet

their need. Lastly, after the start of the EoL care program, it was

important to have regular reviews of the patients who survived longer

than expected.

In the ICUs at US, the assessment or offering of social and spiritual support ranged from 30-61 % [15-17].

In this study, there was a scarcity of such support to patients'

families both before and after the death of the patient. One study has

shown that the use of a brochure on the subject of bereavement together

with a proactive family conference could enable the families to feel

supported and to decrease the Post-Traumatic Stress Score 3 months after

the death of the patient [18]. Holistic care for the family of critically ill patients during EoLC was one of the major areas for improvement in our ICU.

The limitations of this study were it was a small

retrospective case series; the indicators used were not validated in

other studies; and it only reflected the perspective and practice of

EoLC among the Chinese at Hong Kong. Easy to implement quality

indicators were important as they might help to highlight the quality

gap in EoLC in the ICU. With the use of these indicators, it helped to

identify any missing links between the translation of guideline or

policy into quality care to critically ill dying patients in the ICU.

For more articles in Journal of Anesthesia

& Intensive Care Medicine please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/jaicm/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/jaicm/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment