The Conversion from Continuous Sufentanil Infusion to Oral Retarded Opioid Medication: Beware of the Equi-Analgesic Opioid Ratios - A Case Series-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Journal of Anesthesia

Abstract

Background: Sufentanil has an outstanding

place in clinical practice and one cannot think of surgery or intensive

care therapy without it. However, the routine use of continuous

sufentanil infusion may cause severe problems if stabilized patients are

discharged from the ICU after surgical treatment and need to be

converted to oral opioids.

Aim & method: Here we report our

experiences with a series of six patients that we have converted from

intravenous sufentanil to oral morphine.

Cases: In 6 cases, we report intensive care

(ICU) patients after surgical or medical therapy, who received

sufentanil infusion for analgosedation. The patients were between 45 and

68 years old. It can be demonstrated that the optimal dose of

sufentanil can be converted to minor doses of oral medication than

expected from the calculated equi-analgesic ratios. Despite of lower

oral opioid medication pain levels did not increase after conversion.

Conclusion: We recommend to begin opioid

conversion with 10% of the calculated equivalent dose of intravenous

sufentanil when converting to oral long-acting morphine and afterwards

to further adapt the dosage.

Introduction

Since its development in the late 70s, sufentanil has

an outstanding importance in clinical practice and one cannot think of

surgery or intensive care routines without this treatment. The substance

delivers a much higher potency than its parent drug fentanyl with an

expanded therapeutic range [1,2].

From the beginning of its clinical use, sufentanil was the intravenous

opioid of choice for hemodynamically instable patients [3].

Due to its outstanding hemodynamic stability resulting from a minor

impact on cardiac index, left ventricular ejection fraction and heart

rate [4],

sufentanil is broadly used for critically ill patients in cardiac and

non-cardiac surgery. In comparison with fentanyl, it has a shorter

context-sensitive half time that results in better controllability [5] and predisposes the use of sufentanil in extended cases and for continuous infusion in intensive care.

The decoupling of analgesia and respiratory depression [6]

is another reason for preferring sufentanil during weaning of

mechanically ventilated patients or in those with spontaneous breathing.

However, the routine use of continuous sufentanil analgosedation in the

ICU may result in the problem that stabilized patients are still not

free of pain or suffer from chronic pain and thus need to be converted

to oral opioid medication, if discharged from the ICU after surgical or

medical therapy. For example, common dosage of 20μg of sufentanil per

hour has to be substituted by oral opioids as the patient should be

transferred to the floor. The calculated equivalent dose for oral

substitution would be 1440mg morphine per day, which is, of course, not

practicable.

The following cases should demonstrate that

sufficient pain therapy can be achieved also with significantly lower

morphine doses. We report here six cases in which the hospital pain

service was consulted to assist non-anesthetic intensive care units in

the conversion from intravenous sufentanil to oral medication.

Case Presentation

Case 1: Patient J.S., male, 44 years old, weight 170kg, height 175cm; septic shock with multi-organ failure

The patient who suffered from arterial hypertension,

atrial fibrillation, type-II-diabetes mellitus and morbid adipositas was

admitted due to severe and rapid deterioration of his general

condition. He developed a septic shock with subsequent multiorgan

failure including renal insufficiency requiring dialysis, and liver

failure. Furthermore, he developed a cardiogenic shock with a left

ventricular ejection fraction of about 10%, and required

cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) as ventricular fibrillation

occurred.

After improvement and when the patient was able to be

transferred to the floor, he received sufentanil infusion with 25μg per

hour. The patient reported pain scores between NAS four and eight with

burning quality. Pain therapy was converted orally to long-acting

morphine (MST®, Mundipharma Ltd., Limburg an der Lahn, Germany) 3x100mg

and 30mg mirtazapine (REMERGILSolTab®, MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH, Haar,

Germany) in the evening and short-acting morphine(Sevredol®,

Mundipharma Ltd., Limburg an der Lahn, Germany), 20mg up to six times

daily on demand. After a stepwise reduction of the morphine dose down to

3x30mg long-acting morphine per day and 30mg of mirtazapine, the pain

service could sign off after seven days.

Case 2: Patient P.M., male, 63 years old, weight 97kg, height 180cm; serial rib fractures with pleural empyema

*This patient received additionally transdermal fentanyl (Durogesic SMAT 75pg/h)

The patient suffered from a traumatic left-sided rib

series fracture and developed pneumonia and a pleural empyema while

under conservative therapy. Secondary diagnoses comprised arterial

hypertension, COPD, type-II-diabetes mellitus and chronic renal

insufficiency. After surgical intervention and intensive care therapy

with prolonged weaning, the patient was presented to the pain service

for conversion to oral opioids. The current pain therapy was 20μg/h of

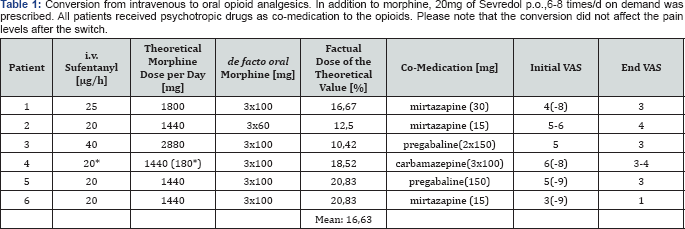

i.v. sufentanil (Table 1).

The patient was switched to 3x60mg long-acting morphine sulphate (MST®,

Mundipharma Ltd., Limburg an der Lahn, Germany) and 15mg mirtazapine

(REMERGIL SolTab®, MSD Sharp & Dohme, Haar, Germany) in the

evenings; additionally Sevredol® 20mg up to eight times daily was

prescribed, if VAS exceeded 5. After a stepwise reduction of the

morphine dose down to 3x30mg with an evening dose of 15mg mirtazapine,

pain service consultation ended after four days, the patient being

satisfied at VAS <4.

Case 3: Patient S.L., female, 53 years old, weight 146kg, height 170cm; sepsis with multiple arterial emboli

The patient was primarily treated for a sepsis with

unknown focus and suffered from morbid adipositas, a history of

hypertension and type-II-diabetes mellitus in the intensive care unit.

During the clinical course, both legs had to be partially amputated due

to multiple arterial emboli; the right leg below the knee, the left leg

above.

Under sufentanil infusion of 40μg/h, the patient was

presented for conversion to oral therapy. The initial regime comprised

3x100mg of long-acting morphine with pregabaline (Lyrica®, Pfizer®,

Berlin, Germany), 2x150mg, and Sevredol®, 20mg up to 6 times daily, if

VAS exceeded 5. The consultation ended after five days, with morphine

dosage reduced to 3x30mg of long-acting morphine and pregabaline

2x150mg. The patient was satisfied at VAS <3.

Case 4: Patient K.K., male, 58 years old,

weight 104kg, height 180cm; osteomyelitis and acute renal failure after

coronary arterial bypass grafting (CABG) surgery

The patient was treated for sternal osteomyelitis and

acute renal failure after coronary arterial bypass grafting. In

addition, the patient suffered from arterial hypertension, peripheral

arterial vascular disease, hyperlipoproteinemia, COPD (GOLD III) and had

been treated previously for laryngeal cancer with laryngectomy and

bilateral neck dissection. At presentation to the pain service for

conversion to oral medication, the patient received 20μg/h sufentanil

with additional transdermal fentanyl (Durogesic SMAT 75μg/h,

JANSSEN-CILAG, Neuss, Germany), which the patient had already before

surgery. Pain scores of VAS=6 with peaks at VAS=8 were reported. The

patient was converted to long-acting morphine 3x100mg/day and

additionally with 3x100mg carbamazepine (Carbamazepin HEXAL®, Salutas

Pharma, Barleben, Germany) with opportunity of receiving supplementary

20mg Sevredol®, up to 8* per day. After reducing long-acting morphine to

2*50mg with carbamazepine 3*300mg, pain service consultation ended

after six days, the patient being satisfied at VAS=3-4.

Case 5: Patient R.S., male, 66 years old, weight 80kg, height 178cm; Multiple Myeloma and ARDS

The patient needed mechanical ventilation support for

acute respiratory insufficiency under pre-existing multiple myeloma.

During the clinical course, the patient developed acute renal failure

requiring dialysis, aspiration pneumonia and critical illness

polyneuropathy. After prolonged weaning, an apparently pain stricken

patient was presented to the pain service receiving 20μg/h sufentanil,

for conversion to oral analgesics.

At pain levels of VAS=5 and peaks of VAS=9, initially

long- acting morphine 3*100mg/day with 150mg pregabaline (Lyrica®,

Pfizer, Berlin, Germany) in the evenings was prescribed, with the

possibility of additionally receiving 8*20mg Sevredol® per day. After

stepwise reduction of morphine dose to 2*20mg/d of long-acting morphine

and 150mg pregabaline in the evenings, the patient was discharged from

the ICU with VAS=3 and the patient was discharged with 2*10mg/d long-

acting morphine and with 150mg pregabaline.

Case 6: Patient K.B., male, 62 years old, weight 60kg, height 160cm; hemorrhagic shock after bypass surgery of the femoral artery

Following bypass surgery of the femoral artery with

secondary hemorrhage and hype volemic shock, the patient developed an

urosepsis. Preexisting diagnoses were peripheral vascular disease,

arterial hypertension, type-2-diabetes mellitus and stage-III-renal

insufficiency. After stabilizing the patient and planning for discharge

to the ward, pain service was consulted for conversion of i.v.

Sufentanil, 20μg/h, to oral medication.

The patient described pain as having

piercing/stabbing qualities at VAS=3, peaking at VAS=9. After a stepwise

reduction of initially 3*100mg/day long-acting morphine with

mirtazapine 15mg for the night, the patient was discharged from the ICU

with 3*60 mg/d long-acting morphine with afore mentioned mirtazapine at

VAS=1.

Discussion

In clinical practice, sufentanil is indispensable for

anesthesia and intensive care therapy. However, a conversion from

continuous sufentanil infusion to oral opioid medication is essential

for discharge from the ICU; however, current literature offers no usable

conversion algorithms.

The pain levels of a series of six patients presented

here indicate that opioid conversion to lower oral doses does not

result in an increase of pain scores. Additionally administered

psychotropic drugs may also have an effect on alleviating pain, yet two

aspects have to be taken into account: (1) pain aggravation by under-dosing of opioids cannot be compensated by psychotropic medication, and (2)

if the opioid dose is titrated to an optimum, psychotropic drugs cannot

further reduce this dose. They can only be used to avoid severe side

effects of opioid therapy [7].

In the present cases, psychotropic medication was used to treat effects

of opioid over-dosing after conventional conversion, and was needed to

treat the neuropathic aspects of the respective pain qualities [8].

It is important to note that the conversion to oral

opioids is not an "opioid rotation", although one has to calculate an

equi- analgetic dose. The concept of opioid rotation addresses the

problem of excessive side effects [9] of a single opioid or the insufficient effect on pain [9,10].

This was not the case in the presented patients. In those, we intended

to switch an i.v. opioid to an orally applied one, much in the way a

morphine drip is switched to oral retarded morphine.

Sufentanil is available as a non-i.v. preparation for

sublingual, buccal and nasal administration but not in a long- acting

formulation. As the application route switch is usually for a single

compound and the long-acting formulation is commercially unavailable,

change to long-acting morphine was necessary, but not in the sense of an

opioid rotation.

In current references, only the general

recommendation to begin oral substitution with approximately 50% of the

equivalent dose can be found [10,11].

These recommendations are based on the thought that on one hand the

patients have not benefitted from the current opioid and on the other

they offer concomitant clinical limitations (i.e. advanced age, renal

damage, cardiopulmonary insufficiency, etc.) that makes a 1:1 switch to a

new opioid inappropriate.

The patients in the presented cases had an i.v.

sufentanil medication near the optimum dose. The available conversion

tables and factors suggested a 900% higher dosing than that we

eventually applied. Even with a reduction of 50% from the given i.v.

dose, the orally administered amount would still have been in excess of

350% of the dose that is finally necessary. This is striking, as

inadequately high doses of opioids can lead to severe side effects such

as attention deficits, optical hallucinations and ultimately respiratory

depression [12,13].

From the present data, we provide evidence that, when

converting i.v. sufentanil to oral morphine, a much steeper reduction

of the equivalent dose is urgently warranted.

We would like to recommend starting with 10-20% of

the calculated equivalent dose of sufentanil infusion when converting to

oral long-acting morphine and afterwards adapting the morphine dosage

further. Possible co-medication with neuroleptics and benzodiazepines

should not be ignored in order to further minimize opioid doses and to

decrease severe side effects.

In the possible case that the conversion to a

long-acting opioid proves insufficient, a similar approach as usually

followed in opioid conversion should be used: In addition to the

estimated dose, rescue medication needs to be provided. This can be

claimed every hour by the patient and, in the case of using morphine

sulfate, doses of 10mg and 20mg with an onset of 15 to 20 minutes should

be available. It seems important that none of our patients claimed

rescue medication.

Conclusion

Owing to safety considerations, we propose to

approach the final opioid dose from a lower dose. By doing this, severe

side effects and a possible readmission to the intensive care unit can

be avoided. Moreover, since the increased pain perception precedes

withdrawal symptoms, correcting the opioid dose in an hourly interval

would not have led to withdrawal indicators [14-18].

For more articles in Journal of Anesthesia

& Intensive Care Medicine please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/jaicm/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/jaicm/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment