Thoughts on Pain Management, Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV) & Brain Fog-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Journal of Anesthesia

Introduction

Persistent anesthesia problems may be summarized as

over- and under-medication, pain management, and postoperative nausea

and vomiting (PONV).

Over- &Under-Medication

Prior to the 1996 FDA approval of a direct cortical

responsemonitor (DCRM), determination of anesthetic dose relied on body

weight, medical & physical assessment (i.e. ASA status), and heart

rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) changes, especially thesevital signs

changes occurring with initial incision.

The cerebral cortexis the target of anesthetics. The

adult brain weighs approximately 3-4 pounds and doesn't vary

substantially with body weight.Average body weight doses based on the

'70 kg' patient will likely over or under-medicate many patients. ASA

status is also an unlikely guide to individual cortical responses to

body weight based drug doses.

Pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) as well as target controlled infusion (TCI) are alternative, yet indirect,

measures of cortical response by way of predicting anesthetic blood

levels. These approaches would be acceptable if blood levels, not the

cortex, were the anesthetics' target.

Vital signs (i.e. HR and BP) are brain stem

functions. The American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) awareness

with recall study showed that half of patients who experienced awareness

had no change in either HR or BP with which to alert their

anesthesiologist [1].

This finding was not an especially surprising since consciousness,

memory and pain perception are cortical, not brain stem, functions.

Under-medication is estimated to occur in only 0.1%

of patients and may result in PTSD in them. Unpleasant an experience as

awareness with recall can be, there are no documented cases of death

from anesthesia awareness. Many of the remaining 99.9% of patients may

be subjected to routine over-medication ( Figure 1).

Not only does one American patient every day perish

(mortality) from anesthesia over-medication but also 16M of the 40M

patients (40%) every year emerge with 'brain fog' (morbidity) [2].

Brain fog may be defined as delayed anesthetic emergence, but also can

include postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) or even delirium [3-5].

Postop brain fog creates additional morbidity while

adding substantial additional costs to the health care system caring for

patients who cannot be quickly processed and discharged from the

system. Additionally, patients must endure the long-term consequences of

their anesthesiologists’ short term care.

The DCRM has been validated in over 3,500 published

studies and can be found in 75% of US hospitals. The question remains

'why is directly measuring the organ being medicated with a DCRM monitor only routinely done 25% of the time?’

Part of the answer may lie in the manner in this

monitor was originally configured. On a unit-less scale of 0-100, the

lower the number, the more sedated the patient. This number is a derived,

not directly measured, value. The 15-30-second delay from real time

places the anesthesiologist in the unfavorable position of catching up

to patient needs instead of being able to anticipate them. This creates a

situation like trying to drive one's car with only the rearview

mirror's information, not especially safe or useful ( Figure 2).

The first anesthesia textbook with a DCRM monitor on its cover also displayed the electromyogram (EMG) of the frontalis muscle (akin to the EKG of the cardiac muscle) in the picture ( Figure 3).

The text described the utility of this real-time signal; i.e. EMG

spikes signal incipient arousal and the need to proactively increase

sedation to return the EMG to baseline [6]. All that is needed to display the EMG is to use the existing software to select and save it as the secondary trend.

Most patients achieve propofol sedation adequate

enough to prevent awareness and recall at 60<BIS<75 (with baseline

EMG) level of with 25-50 mcg-1 .kg'1 .min. Over 18-years’ experience titrating propofol with DCRM, variation of as little as 2.5 mcg-1 .kg-1 .min and as much as 200mcg-1 .kg-1

.min has been observed to achieve the same level of amnesia and

sedation. ‘Apples’ to ‘apples’ comparisons between patients, despite the

nearly hundred-fold observed variation in propofol requirements

to achieve, become more meaningful when using numerically based

definitions of levels of consciousness achieved [7].

Postoperative brain fog likely is a multi-factorial

problem. Until universal DCRM monitoring becomes a standard of care, it

will not be possible to clarify the role routine over-medication plays [8].

It is unlikely beneficial for elderly patients to routinely administer

30% more than what is needed to achieve 60<BIS75. Common sense is

uncommon ( Figure 4) - Voltaire.

Pain Management

Most people know it does no good to close the barn

door after the horses have escaped. But too many anesthesiologists still

need to be convinced that it’s futile to try to prevent postop pain by

allowing surgeons to cut without first blocking the midbrain N-methyl,

D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors [9,10].

Local anesthetic skin injection or incision is an extremely

potent signal to the brain that the "world of danger" has invaded the

"protected world of self." The sedated brain can’t differentiate between

the mugger’s knife and the surgeon’s scalpel (or trocar). While there

are certainly other internal pain receptors, no signal is more

determinant of post-operative pain than of skin incision (or skin

injection). An unprotected incision sets off the major cortical

alarmsthat initiate the wind-up phenomenon.

Surgery is a painful experience.Most

anesthesiologistsbelieve acardinal function is the prevention of pain

during surgery. From 1975 through 1993, this author had never once

considered why there was a need for postop opioid rescue for many, if

not most, patients. In 1992, a clinical trial began using 50 mg IV

ketamine, 2-3 minutes prior to stimulation AFTER propofol hypnosis to

dissociate patients for pre-incisional local anesthesia injection [11,12].

When propofol is incrementally titrated ketamine hallucinations are eliminated [13]. For elective surgery, customary propofol increments are 50 mcg-1.

kg repeated either to loss of lid reflex/loss of verbal response or to

60<BIS<75 with baseline EMG. This DCRM level is usually attained

within 2-3 minutes. Starting with such an apparently homeopathic

propofol dose quickly allows the anesthesiologist to determine an

extremely sensitive patient and avoid prolonged emergence and, likely,

less brain fog.

The benefit of incremental induction is creating a

stable CNS level of propofol to protect from ketamine side effects,

preservation of spontaneous ventilation, maintenance of SpO2, and not creating the difficult airway [14]. Incremental propofol induction most commonly preserves the tone in the masseter, genioglossus and orbicularis oris muscles, maintaining a patent airway. Absent a propofolbolus induction, baseline blood pressureis also maintained.

After observing the first 50 cases emerge without opioid rescue, it was reasonable to concludethe principle reason patients have pain after surgery is that they've had pain during surgery. The lack of opioid rescue continued over the next 1,214 patients [15] and through to the present day of more than a total 6,000 patients.

Dissociation, or immobility to noxious stimulation,

results from mid-brain NMDA blockadelmmobility (i.e. dissociation) has

beenconsistently observed in 100-pound female patients and 250-pound

male patients with the same 50 mg ketamine dose.

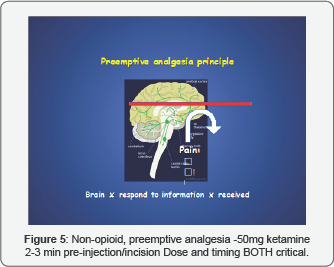

Why does the effective dissociative dose of ketamine

not appear to be related to body weight? The adult brain weighs

approximately 3-4 pounds and doesn’t vary with body weight. The midbrain

is a very small part of the adult brain, and the NMDA receptors are a

very small part of the midbrain. Pre-stimulation NMDA block denies the

cortex the knowledge of the intrusion of the outside world of danger.

Cognitive dissonance generated by thelack (or

dramatically) reduced opioid rescue with pre-stimulation ketamine dose

is so great that many, if not most, anesthesiologists will need to

observe 10-20 cases to believe them. However, the PACU RNs will notice

more quickly. Surgeons and patients' family members will be as impressed

as the recovery personnel.Once the patient is protected as described

above, the non-opioid, 50mg ketamine ‘miracle’ is achievable with

propofol sedation, regional analgesia/propofol sedation, and general

inhalational anesthesia ( Figure 5).

Postoperative Nausea & Vomiting (PONV)

Much has been written about postoperative nausea and

vomiting (PONV). In 1996, Apfel identified the four most predictive PONV

factors; namely, non-smoking, females, history of PONV, planned use of

postoperative opioids [16]. Apfel subsequently referenced Friedberg's 1999 study [15] in his PONV chapter [17,18].

Apfel's PONV chapter is number 86 of 89 chapters in Millers' Anesthesia.

While patients do not die from PONV, they only wish they were dead.

Greater importance to PONV needs to be heeded by our profession as

patient satisfaction now plays a role in government and other third

party reimbursement.

The data for this five-year review documenting a 0.6%

PONV rate (i.e. 7 of 1,264 patients) were collected by 1997 but not

published until 1999 [15].

These patients turned out to be an Apfel-defined high PONV risk patient

population that received no anti-emetics! No intra-operative opioids or

inhalational ('stinky gases') agent were used [19]. Postoperative opioids were routinely prescribed but rarely used.

Analgesia was provided with adequate local

analgesia. Spontaneous ventilation was preserved using only a single

respiratory depressant, propofol, and scrupulously avoiding

intra-operative opioids. no patients received neuromuscular blocking

agents. This left the possibility of patient movement.

Patient movement under sedation is usually the cause

for great stress on all involved with the surgery, especially the

surgeon who may have pre-operatively injected the operative field with

syringes of lidocaine and epinephrine. Observing vasoconstriction, the

surgeon (incorrectly) surmises adequate analgesia is present and clamors

for more sedation.

The anesthesiologist usually responds with a request

for additional analgesia. Tempers rise leading to the inappropriate

addition of opioids, benzodiazepines etc. or worse, the abandonment of

sedation in favor of general anesthesia (GA) with muscle relaxants. None

of these maneuvers treat the movement most accurately.

The presence or absence of an EMG spike on the DCRM enables a dispassionate

discussion of what the patient most accurately (and minimally) needs to

return the patient to the desired motionless condition. In the pre-DCRM

era, all patient movement was treated as if it could be awareness and

recall. As seen with the headless chicken, a brain is not necessary to

generate movement ( Figure 6).

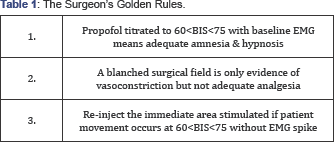

There exists no spinal reflex that can stimulate the EMG of the forehead frontalis muscle. Patient movement without an EMG spike can only be generated by sub-cortical stimulation. This Surgeon's Golden Rules ( Table 1)

needs the anesthesiologist’s time preoperatively with the surgeon to

assure success without increasing the known risks of GA. This author

believes it is very difficult to accept GA risks for patients having

surgery without medical indication; i.e. elective cosmetic surgery. A

more enlightened approach is possible using the absence of the EMG spike

with patient movement to refute the notion that the patient is 'too

light' ( Figure 7) ( Table 1).

Conclusion

When you can measure what you are speaking about, and

express it in numbers, you know something about it; but when you cannot

measure it, when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of

a meager and unsatisfactory kind; it may be the beginning of knowledge,

but you have scarcely, in your thoughts, advanced to the stage of

science.

William Thompson, knighted Lord Kelvin.

Popular lectures and addresses 1891-1894

Less is more. - Mies van Der Rohe

Without direct cortical measurement of anesthetic

effect, neither science nor minimally trespassing on patients’

physiology will occur. Predictably, problems like over and

under-medication, postoperative pain management and PONV will continue

to plague anesthesiologists and their patients while incurring avoidable

costs. Propofol measurement to 60<BIS<75 with baseline EMG

obviates the perceived need of the commonly used 2 mg midazolam

premedication. Eliminating midazolam also eliminates prolonged emergence

in sensitive and/or elderly patients.

Direct cortical response measurement enables

anesthesiologists to treat patient requirements as the individuals they

are as opposed to the 80% of patients in the middle of the bell curve.

Doing so eliminates outliers, transforms every patients’ ‘mystery’ into

an ‘open book test,’ and creates the basis for more humane, cost

effective anesthesia care.

Over twenty-five years and in more than 6,000

patients, there has not been a single hospital admission for brain fog,

postoperative pain management or PONV. Friedberg’s Triad does indeed

appear to answer anesthesia’s persistent problems.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Friedberg is the president and founder of the

nonprofit Goldilocks Foundation. Neither he, nor the foundation,

receives financial support from brain monitor makers. Dr. Barry

Friedberg has been interviewed extensively about anesthesia and propofol

by FOX, CNN, True TV, and People Magazine during the MichaelJackson

murder trial. A board-certified anesthesiologist for 39 years, Dr.

Friedberg developed propofol ketamine (PK) anesthesia in 1992 and made

PKnumerically reproducible with the addition of the anesthesia brain

monitor (aka Goldilocks anesthesia) in 1998. He has been published and

cited inseveral medical journals and textbooks and was honored with a

U.S. Congressional award for applying his methods on wounded soldiers in

Afghanistan and Iraq.

For more articles in Journal of Anesthesia

& Intensive Care Medicine please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/jaicm/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/jaicm/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment