Anaesthetic Recommendations for Stiff Person Syndrome-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Journal of Anesthesia

Abstract

Background: Stiff person syndrome (SPS) is a neurological condition with serious implications during anaesthesia if overlooked.

Objective: Our purpose was to highlight the

issues encountered during anaesthesia in patients with SPS and to

evaluate the most appropriate anaesthetic management during surgery.

Methods: A structured search was performed

throughout various databases such as Ovid medline, Pubmed, Embase and

Cochrane Collaboration for articles published from 1950s and after. The

search included only humans and those who underwent procedures with

anaesthesia.

Results: Only 13 of such case studies were

found due to the rarity of the condition. Amongst these 13 patients,

most were in the middle to elderly aged groups and they underwent

different procedures. Their response to different drugs used for

induction, neuromuscular blockade or maintenance of anaesthesia also

varied with some leading to life-threatening complications especially

due to postoperative hypotonia. Route of anaesthesia also had a role in

changing the outcomes.

Conclusion: SPS is challenging to manage and

the use of drugs like midazolam, propofol, rocuronium is recommended to

improve patient outcomes. Volatile agents are safe if their doses are

kept to a minimum with bispectral index monitoring. Alternative routes

of anaesthesia may be better but this is not always feasible.

Keywords: Stiff person syndrome; General anaesthesia; Neuromuscular blockers; Inhalational anaesthetics; Surgery Introduction

Stiff person syndrome (SPS) is a unique neurological disorder first described in 1956 by Moersch & Woltman [1]. It has no known genetic predisposition [2] but an association with certain HLA genes exists [3]. SPS is slowly progressive with insidious onset, which commonly begins in the middle-age [4-6]. It is typified by stiffness and rigidity of the axial and proximal limb musculature, with superimposed painful spasms [2,3,6]. In more severe cases, the muscles of respiration and swallowing are affected and may cause respiratory distress [5,7].

The painful spasms can be triggered by external sensory stimuli, voluntary movement, fear, anxiety [8,9]

and appear to arise from the brain or spinal cord because they stop

during general anaesthesia (GA) or sleep. The aetiology of SPS seems to

be autoimmune as circulating autoantibodies reactive with glutamic acid

decarboxylase (GAD) have been found in SPS patients [10,11].

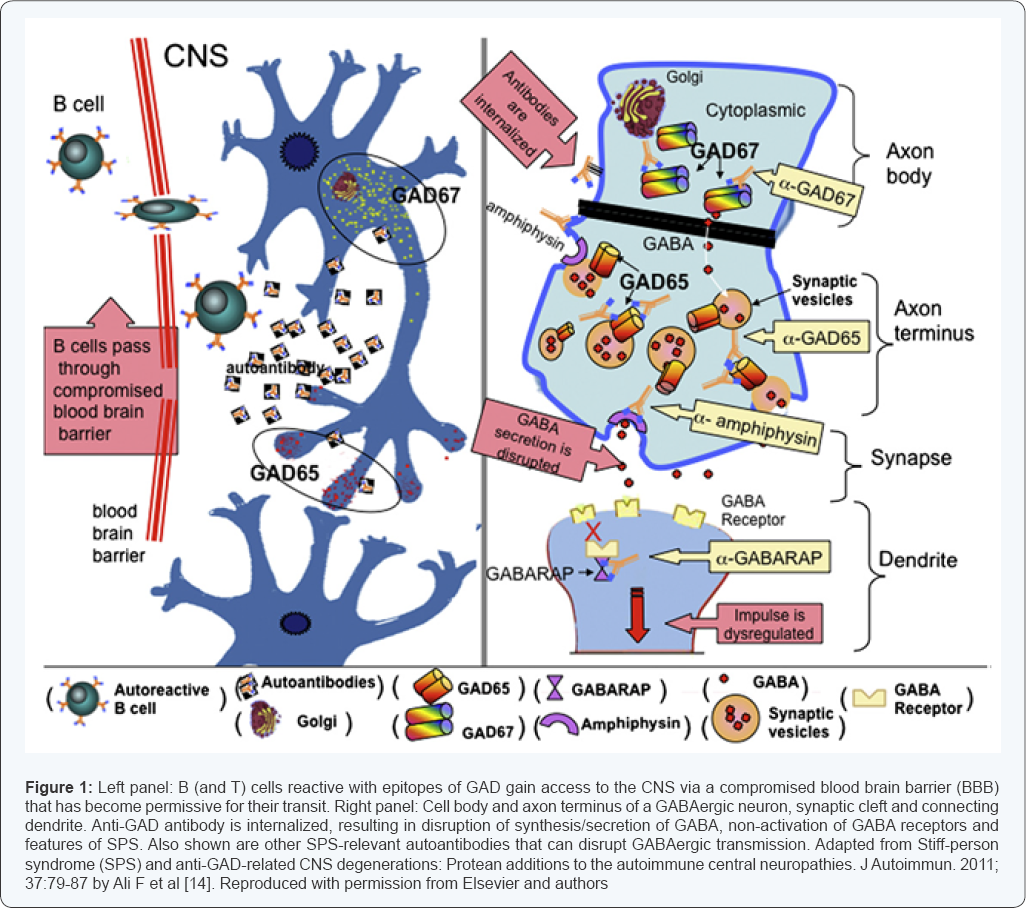

GAD is an enzyme necessary for the production of gamma-aminobutyric

acid (GABA). GABA has an inhibitory (gabanergic) input to muscles

causing a muscle relaxant effect. Reduction in GABA production upsets

the balance of excitatory inputs in various areas of the brain,

specifically the gamma- motor neuron system, leading to continual motor

neuron activity and spasms [12,13]. Figure 1 illustrates the action of anti-GAD antibodies [14].

Drugs enhancing central gabanergic neurotransmission

such as diazepam are used in treating SPS because it increases the

frequency that GABA receptors are activated. Baclofen synergises with

diazepam and is prescribed together. Similarly useful drugs include

clonazepam and sodium valproate [5,15]. Other treatments inducing remission involve immunosupression with steroids [5] or rituximab [16].

SPS if overlooked may lead to serious problems with anaesthesia. The mechanism of rigidity involved is different from

malignant hyperthermia which has a rapid onset of symptoms often triggered by various anaesthetic agents [17,18] and SPS should not be a contraindication for surgery. Careful monitoring and choice of anaesthesia is still essential.

The principal aim of this review is to provide

recommendations in the anaesthetic management of a patient with

Stiff-Person Syndrome (SPS) during surgery. Additionally, a literature

review and suggestions on how to choose anaesthetic drugs in order to

avoid postoperative complications will be discussed.

Methods

A structured search was performed through Ovid

medline, Pubmed, Embase and Cochrane Collaboration; this includes

articles in English language published from 1950s until the present. A

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) search within titles and abstracts with

keywords such as "Stiff man syndrome", "Stiff person syndrome", "SPS",

"SMS", "Anaesthesia", 'Anesthesia", "Anaesthetics" and "Anesthetics" was

done.

The search was limited to include only studies involving humans.

Results

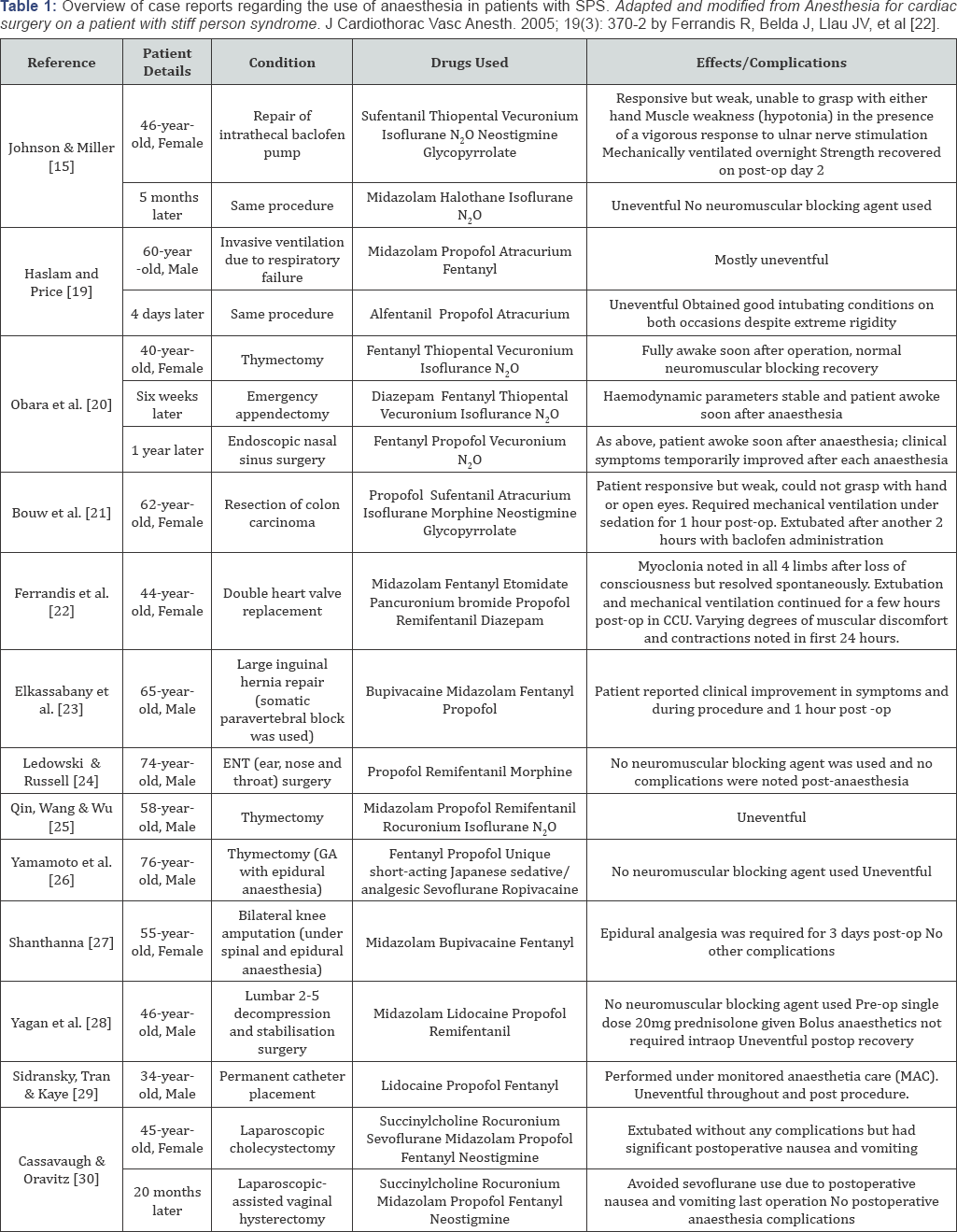

There are no randomised controlled trials or

case-control studies involving the effect of anaesthetic drugs in SPS

patients or recommended anaesthetic drugs of choice. Nevertheless, there

were 13 case reports describing peri- and intraoperative management of

SPS patients; with some studies highlighting the increased risk of

postoperative hypotonia as shown in Table 1 below.

Discussion

Firstly, the use of appropriate temperature

monitoring and regulation during surgery for SPS patients with the aid

of a Bair hugger is recommended. As baclofen is the mainstay therapy for

SPS, such patients would have poor temperature perception. Oliviero et

al. [31]

showed that long-term baclofen therapy would impair temperature

perception as it increases both the threshold for warm and cold stimuli.

This occurs because baclofen activates receptors for GABA-B which

modulates temperature perception.

For induction, propofol is a safe choice and other alternatives include halogenated gases, thiopental, propofol and etomidate [32]

which act via the gabanergic pathway. Such agents should reduce

postoperative muscle spasm or pain in SPS patients, who have decreased

gabanergic input. Etomidate has been reported by Ferrandis et al. [22]

to have a higher risk of intraoperative myoclonus. This reflects

neuromuscular hyperexcitability but it is unclear whether SPS

perpetuated the myoclonus [22], or if etomidate had an idiosyncratic effect. Diazepam, fentanyl and atropine have been prescribed as pre-medication [33] to overcome myoclonus in non-SPS patients but Ferrandis et al. [22]

reported that these were ineffective in their SPS patient. A higher

dose of benzodiazepine could have been useful but there is insufficient

literature to support this [22].

Propofol has also been implicated in case reports to cause intraoperative myoclonus [34-36] but it has a lower risk. A randomised controlled trial by Miner et al. [37]

reported that 18.2 % more (95% CI 10.1% to 26.2%) non-SPS patients who

received etomidate had intraoperative myoclonus compared to those on

propofol. Moreover, propofol improves postoperative muscle rigidity and

spasms as reported by Obara et al. [20]. The published literature suggests that propofol reduces spinal activity [38] by acting primarily on GABA-A receptors [39-41] with some partial effect on central GABA-B receptors [42-44] unlike baclofen, which is a selective GABA-B receptor agonist [45-47].

Propofol would be the drug of choice for anaesthesia

induction in SPS patients with the concomitant use of midazolam, which

also modulates GABA-A receptor activity [43]. Pre-medication is not necessary since these SPS patients would have already been managed with diazepam and baclofen.

Muscle rigidity in SPS patients can make it difficult to position a patient for intubation [19]

during general anaesthesia. Thus there is a role for neuromuscular

blocking drugs. However, Johnson and Miller reported that the use of

vecuronium, (a non-depolarising neuromuscular blocking drug) caused

postoperative hypotonia [15].

This led to their patient requiring mechanical ventilation for 48 hours

despite attempts to reverse the neuromuscular blocking drug. This

complication was not observed by Obara et al. [20], Haslam & Price [19].

Haslam and Price used atracurium but did not encounter similar

complications as described by Johnson and Miller. Johnson and Miller

reported that the mechanism behind their patient's postoperative

hypotonia was unclear but claimed that it did not occur when they

performed the same procedure without neuromuscular blocking drugs. Their

patient also had a past surgical history of prolonged postoperative

weakness when she had her baclofen pump inserted but this was attributed

to baclofen overdose [15].

This particular patient could be idiosyncratic for

having very sensitive GABA-B receptors. Moreover, the dose of thiopental

used in their patient was 5.8mg/kg compared to Obara et al. [20] who only administered 3mg/kg even though they used the same amount of vecuronium (8mg) in their respective patients [15,20].

The additive effect of using a higher dose of anaesthesia at induction

combined with their patient's idiosyncrasy could explain the cause

behind the complications that Johnson and Miller experienced.

Anti-GAD antibodies have no action at the neuromuscular junction, according to Figure 1 [14], hence, neuromuscular blocking drugs would not potentiate their effect. Obara et al. [20]

confirmed that their patient achieved a 25% twitch recovery time (which

was within their patient's normal range) while on vecuronium. Their

patient's train-of-four (TOF) ratio (which indicates depth of

neuromuscular blockade) monitored in the ulnar nerve also recovered to

100% postoperatively. This suggests that the neuromuscular junction was

not affected by SPS [20]. Yamamoto et al. [26]

who did not administer neuromuscular blocking drugs as they were using

epidural anaesthesia in conjunction with GA, also ascertained that the

neuromuscular junction was unlikely to be affected in SPS as their

patient’s TOF ratio remained above 90% throughout the anaesthesia.

Ferrandis et al. [22]

found that the pharmacodynamics of neuromuscular blocking drugs in SPS

was not clearly described in literature. They added that the effect of

neuromuscular blockers used in the cases reported by Johnson and Miller,

Obara et al. [20] was neither greater nor longer lasting than normal. In contrast, Ferrandis et al. [22]

reported longer response and recovery time to the TOF after the

administration of a second dose of 4mg of pancuronium, before ending

extracorporeal circulation for cardiac surgery. They had earlier given

8mg of pancuronium for intubation with normal response and recovery time

to the TOF. Ferrandis et al. [22]

claimed that extracorporeal circulation could possibly have prolonged

the effect of neuromuscular blocking agents. It could also explain why

their patient was mechanically ventilated for a few more hours

postoperatively.

There does not appear to be any anaesthetic

interactions or additional contraindications to use neuromuscular

blocking agents in SPS patients. A recent case reported by Cassavaugh

and Oravitz had successfully managed a patient with both

depolarising and non-depolarising neuromuscular blocking agents on

separate procedures with TOF monitoring [30].

The patient did not experience any postoperative complications. Careful

individual monitoring of neuromuscular response in the form of TOF is

more important and rocuronium/ vecuronium would be the recommended drug

of choice which can be reversed promptly by sugammadex even in

situations of profound neuromuscular blockade [48].

Regarding the hypotonia in Johnson and Miller's patient, Bouw et al. [21] attributed this to baclofen amplifying the gabanergic effects of volatile agents during GA. Bouw et al. [21]

reported that their patient who was usually on baclofen developed

muscle weakness and required mechanical ventilation for 1 hour

postoperatively and suggested the 0.6-1.0% isoflurane as the cause.

Similar postoperative complications were described in a patient who did

not have SPS and received the same drugs [49]. Animal studies have also proved that baclofen potentiates the effects of halogenated agents [50]. Volatile anaesthetics enhance gabanergic input by extending postsynaptic inhibitory currents when GABA is released [51,52]. Since SPS patients are on baclofen for treatment, the doses of such anaesthetic agents should be adjusted. Bouw et al. [21]

also confirmed on pharmacokinetic analyses that neuromuscular blocking

agents and opioids did not play a role in the complications observed.

Not all reported cases had significant adverse

outcomes; Cassavaugh and Oravitz did not encounter any respiratory

problems with sevoflurane use [30].

Qin, Wang and Wu also reported a case of paraneoplastic SPS requiring

thymectomy which did not develop any prolonged postoperative hypotonia

or weakness. They attributed this mainly to the low concentration of

isoflurane used (0.2-0.4%) as they used a target-controlled infusion of

remifentanil and nitrous oxide for maintenance

[25]

. This is a useful method of minimising the concentration of volatile

agents but it is not tailored to individual patients. A better strategy

to overcome this was reflected in the case reported by Yamamoto et al. [26]

who used the bispectral index (BIS) to monitor the minimum

concentration needed. These gases may cause postoperative hypotonia when

used in combination with ongoing baclofen therapy but their

concentration can be kept to a minimum with BIS monitoring. This

approach would allow the continued use of these agents with reduced risk

of respiratory failure.

Different routes of anaesthesia may help as suggested by Yamamoto et al. [26] and Shanthanna [27]

who both used epidural anaesthesia which alleviated postoperative pain

effectively in their SPS patients. Adequate pre-medication is necessary

to prevent spasms caused by the pain on needle insertion [26,27], although therapeutic medications for SPS such as baclofen and diazepam may be sufficient. Yamamoto et al.

[26]

reported that explaining epidural anaesthesia to the patient

preoperatively reduces fear and anxiety which can induce SPS symptoms.

Shanthanna [27] advocated that using conscious sedation would also keep the patient calm. Elkassabany et al. [23]

demonstrated that somatic paravertebral blockade in their SPS patient,

supplemented with conscious sedation, also prevented postoperative

hypotonia. Spinal anaesthesia is an alternative but Shanthanna suggested

using lower doses to reduce the risk of respiratory distress from a

high spinal anaesthesia, especially in SPS patients who have rigid chest

wall muscles [27].

Great care should be taken when administering spinal or epidural

anaesthesia in SPS patients who have an intrathecal baclofen pump.

Lastly, another route of anaesthesia that has

successfully managed a SPS patient requiring GA was total intravenous

anaesthesia (TIVA). Ledowski and Russell reported that it did not lead

to any postoperative hypotonia or SPS symptoms of muscle rigidity or

spasms [24].

Their patient was undergoing ENT surgery and was administrated propofol

with high-dose opioids which obviated the need for neuromuscular

blocking drugs [24]. Yagan et al. [28]

also followed a similar routine for an orthopaedic procedure without

neuromuscular blocking drugs for intubation and achieved good outcomes.

However, this method may not be applicable in all kinds of surgery,

especially abdominal surgery.

Conclusion

SPS is a rare disease that can present challenges in

anaesthesia due to its effects on the GABA pathway. While minor

procedures can be performed under monitored anaesthetic care with IV

sedation [29],

major cases would require TIVA and RA (with or without conscious

sedation) or a combination of both are possible ways to prevent

postoperative hypotonia or mechanical ventilation but may not be

feasible in all types of surgery. Explaining the procedure and surgery

to the patient with the use of midazolam at induction can keep the

patient calm and relaxed to prevent triggering any SPS symptoms. The use

of propofol at induction with the regular opioids for maintenance of

anaesthesia would be a suitable combination for SPS patients. Volatile

gases may be safe for maintenance too. Rocuronium can also be utilised

especially for difficult intubations with sugammadex at hand if

necessary.

Another recommendation would also be the need for

continuous monitoring of patient parameters such as TOF and BIS which

aid in keeping the doses of neuromuscular blockers and volatile

agents/propofol to a minimum respectively. This is particularly crucial

for patients on long-term baclofen who would also require appropriate

temperature regulation during surgery. Admission to ICU postoperatively

would be pertinent for any major or complicated procedures to check for

any respiratory or muscular complications and to regulate the

readministration of preoperative doses of benzodiazepines.

The data on SPS is limited (only 150 cases from 1980 to 2005 have been described in literature [22]).

Other factors to consider during anaesthesia would be comorbidities and

complexity of surgery performed since it may affect choice of drugs and

route. As all the case reports highlighted in this review involved a

different surgery, more detailed trials would be required to confirm

their findings but the incidence of this disease remains extremely low.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the valuable editorial input of Professor Ian Mackay.

For more articles in Journal of Anesthesia

& Intensive Care Medicine please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/jaicm/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/jaicm/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment