A Prospective Cohort Study Comparing Medical Student Intubation on Cadaveric and Manikin Models Using the King Vision™ Videolaryngoscope and Direct Laryngoscopy-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Journal of Anesthesia

Abstract

Objective: Compare intubation by

medical students with direct laryngoscopy (DL) versus King Vision™

videolaryngoscope in training and cadaveric models.

Methods: 24 medical students

with no experience intubating humans were randomized into two groups: DL

first or King Vision™ videolaryngoscope first. Following a short

training, techniques were practiced ona manikin model. Intubation

success, ease of use, and one timed manikin intubation was recorded.

Students crossed, repeated training and trial with other technique.

Students then intubated 3 cadavers with their initial technique, crossed

over to intubate these same cadavers using their second technique.

Cormack-Lehane (C-L) view of the glottic opening, time to intubation,

intubation success, ease of use, and preferred technique were recorded.

Results: In manikin intubation,

success rate was not significantly different. Mean time to intubation

using DL was 19.67 seconds, 11.03 seconds with King Vision™. The median

“ease of use” for DL was 7; King Vision™ was 4 (0 easiest, 10 hardest).

In cadaver model, the median C-L view was 2 for DL, 1 for King Vision™.

Success rates were 82% for DL and 93% for King Vision™. The median “ease

of use” for DL was 5 and King Vision™ was 4.

Conclusion: The King Vision™

videolaryngoscope had statistically significant improved visualization

of the glottic opening, intubation success rate when compared to DL, and

was rated easier to use. Given the portable nature, low cost, ease of

use, and easy maintenance; the King Vision™ videolaryngoscope should be

considered an excellent device for intubation training orany emergent

setting where advanced airway management is required.

Keywords:

Videolaryngoscope; Laryngoscopy; Airway management; Cadaver study;

Manikin study; King Vision; King Vision; Endotracheal intubation;

Medical studentIntroduction

Orotracheal intubation is a critical skill required

to manage patients with airway compromise or respiratory failure.

Traditionally, direct laryngoscopy (DL) has been the standard method

used to intubate patients. DL can be complicated by many factors that

obstruct direct visualization such as pathology to the oropharynx (e.g.

tumor) and limited mobility of the cervical spine [1-5].

Videolaryngoscopes (VL), which provide an indirect view of the glottis

and vocal cords, have been in use as an adjunct to DL for over a decade

[2,6,7]. Due to its ability to see “around the corner” via indirect

visualization of the glottic opening, VL has been recommended for

intubation in patients with limited neck mobility, airway anatomy that

is difficult to visualize, and for training novice intubators in

laryngoscopy [1,2,4-6,8-11]. The King Vision™ VL is a relatively new,

single unit, indirect videolaryngoscope that is lightweight, has a self

contained high-resolution camera, is battery operated, and has a curved

blade with the option of a tube-guiding channel for easier intubation.

Unique to the King Vision™ setting it apart from other VL is its low

cost and portability relative to all other VL.

Objective

The purpose of this investigation was to compare

timing and intubation success of the King Vision™ VL to DL in a manikin

and cadaveric model by medical students with no prior intubation

experience on human beings. Secondary outcomes were ease of use of DL

and the King Vision™ VL in both the manikin and

cadaver model as well as the Cormack-Lehane (C-L) view in

cadaver model only as this is the model that best simulates real

life intubating conditions.

Material and Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board

at the University of Texas Southwestern. This was a randomized

cross-over simulation study design in which 24 first year

medical students with fewer than 5 manikin intubations, not

previously employed in healthcare, and no prior intubation

experience on human beings were randomized into two groups.

Group 1 was initially trained in the use of DL followed by testing

their ability to intubate with DL on a manikin model. Group 2

was initially trained in the use of the King Vision™ VL followed

by testing their ability to intubate with this device on a manikin

model. Then, each group crossed over to intubate with the other

technique using the same training and testing as detailed below.

All training was performed using an adult Laerdal® airway

management trainer (www.laerdal.com).

All participants were recruited by campus wide email

and received no compensation for participation other than

intubation skills training. Exclusion criteria were extensive

intubation experience, defined as 5 or more previous lifetime

attempts, or any prior human intubation experience. After

written informed consent was obtained, each participating

student was required to review an 11-minute DL intubation

video, read a 4-page tutorial on basic endotracheal intubation,

and attend a 10-minute orientation on the King Vision™

VL. Group 1practiced DL intubation using a Macintosh 4

laryngoscope on a manikin model and Group 2 practiced VL

intubation using the King Vision™ VL with a channeled blade

until each student demonstrated 3 successful intubations and

felt comfortable with their assigned technique. Students then

had a timed intubation on the same manikin that they practiced

their assigned technique. The time to intubation and success

rate was recorded. The time period started once the tip of the

laryngoscope passed the lip of the manikin and ended once the

student verbalized that the intubation was complete. A research

assistant confirmed endotracheal tube placement in the manikin

via direct visualization. After completing a timed intubation on

their assigned technique, each student completed a written

survey to assess their perceived ease of use for that intubation

technique using a 0-10 scale with 10 being “very difficult” and

0 being “easy.”The students then crossed over techniques and

repeated the intubation training, testing and survey.

Students were then assigned to 3 of 6 cadavers, each

intubating all 3 assigned cadavers with the first technique,

then crossing over to intubate these same 3 cadavers using the

other technique. Students were asked to assess the C-L view of

the cadaveric glottic opening for each timed intubation with

each technique. As described in 1984 by Drs. Cormack and Lehane, the C-L view was graded as follows: 1) Grade 1, most

of the glottis is visible, 2) Grade 2, only the posterior extremity

of the glottis is visible, 3) Grade 3, no part of the glottis (only

the epiglottisis visible), and 4) Grade 4, not even the epiglottis

can be exposed [12]. The following information was recorded

for the cadaver intubations: time to intubation as described

above with the manikins, C-L view of the glottic opening, and

proper endotracheal tube (ETT) placement. ETT placement was

confirmed by direct observation of the ETT in the trachea through

a window created in the cricothyroid membrane by investigators,

who were blinded to the study group of the participant during

the intubation procedure. The C-L view was verbalized to the

research assistant present at the time of each intubation. After

completing intubation on the assigned cadavers, each student

completed a written survey to assess their perceived ease of

use of each intubation techniqueas mentioned above with the

manikins. Study was limited to 24 participants due to time,

availability, and materials constraints.

Results

A total of 24 first-year medical students (10 (42%) male, 14

(58%) female) were consented to participate in the study. The

King Vision™ VL is abbreviated as VL in the results section for

the purpose of simplicity.

Manikin data

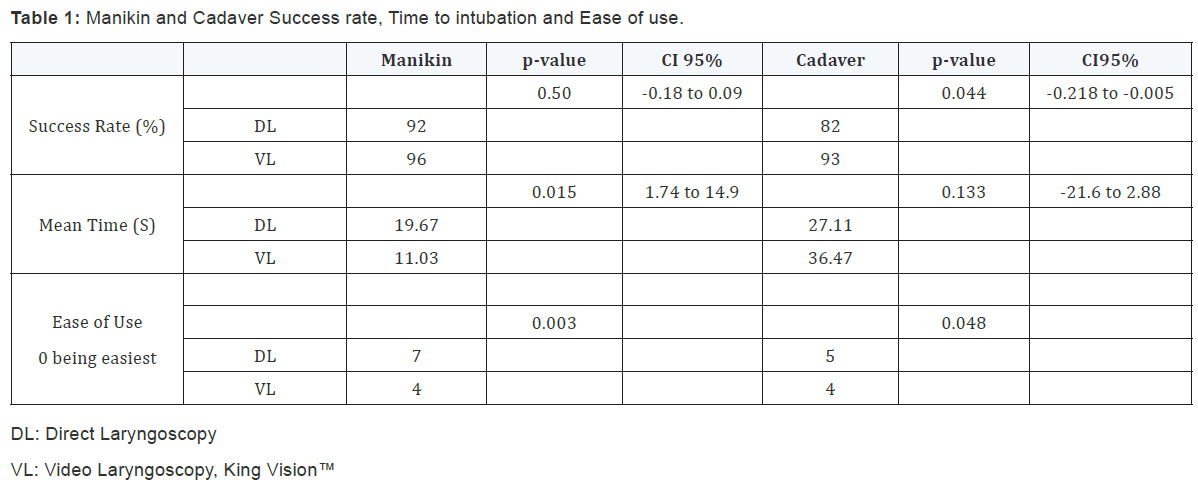

There were 48 measured intubations performed by the

students on manikins, 24 DL and 24 VL. The intubation success

rate was 92% (n = 22) for DL and 96% (n = 23) for VL, p-value

= 0.50 with Fisher’s exact test. The mean time to intubation was

19.67 seconds using the DL and 11.03 seconds using VL, p-value

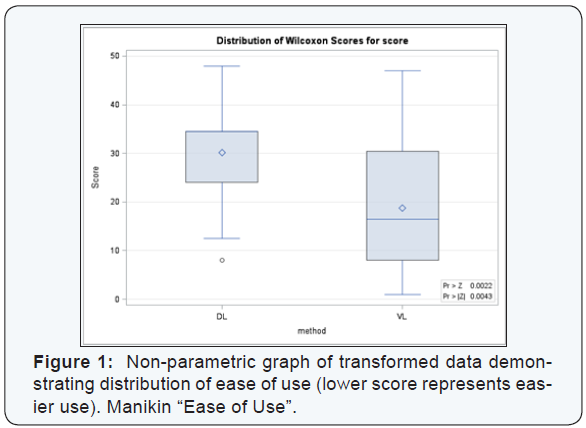

= 0.015 with Student’s t-test, Table 1. Utilizing Wilcoxon Rank

Sum test, the median ranking for “ease of use” was 7 for DL and

4 for VL on a 0 to 10 scale with 0 being the easiest to use and 10

being the most difficult, p-value = 0.003, indicating that students

thought the VL was easier to use, Figure 1 which has transformed

the 0 to 10 scale into a larger scale on the vertical axis to better

demonstrate the distribution of the data.

Cadaver data

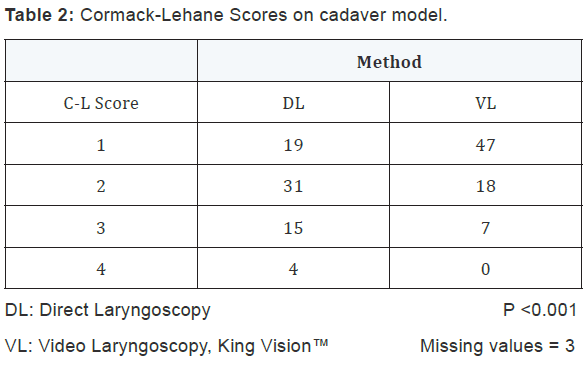

There were 144 cadaveric intubation attempts (all 24

students intubated 3 different cadavers with each technique):

72 DL and 72 VL. The median C-L view grade was 2 for DL and

1 for VL, p-value < 0.001.Generalized Estimating Equations

were utilized for our ordinal values of the C-L grade, Table 2.

Eighteen of the intubation attempts were unsuccessful: 13 DL

and 5 VL. Success rates were 82% (59/72) for DL and 93%

(67/72) for VL, p–value = 0.044, Table 1. Generalized Estimating

Equations were used as successful intubation was a binomial

variable and confirmed that success rates were statistically

higher with the VL method. No statistical difference was seen

in the time to intubation for the method (DL vs. VL), Table 1.

Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance was used to determine

if the time to intubation varied between the DL and VL methods

of intubation for all participants. The intubation technique that

was used first by the student made no significant difference in

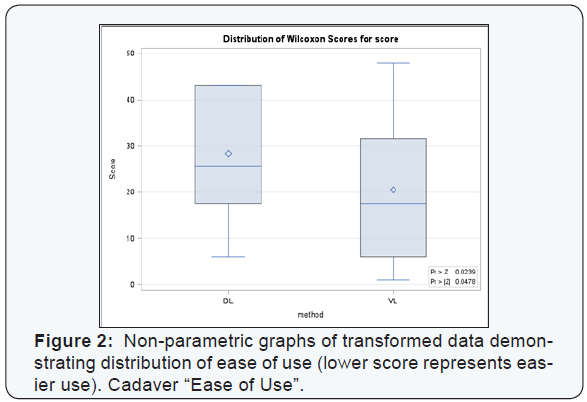

time to intubation or success. “Ease of use” for the cadaver model

utilizing the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test demonstrated that the VL

was also easier to use in the cadaver, p=0.048 Table 2 & Figure

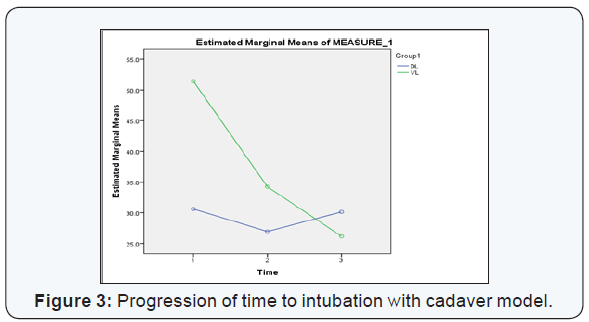

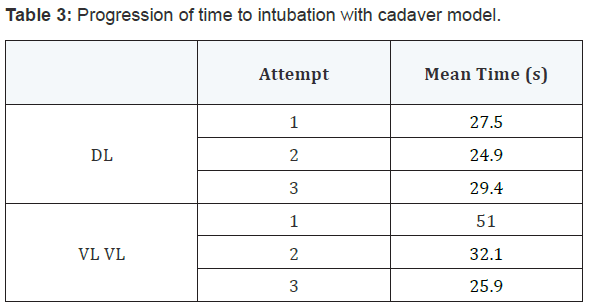

2. There was a positive trend in mean time from the first to third

intubation with VL from 51.0s to 25.9 s. DL had no improvement

with repeat intubation Table 3 & Figure 3.

Discussion

The results of the current investigation clearly demonstrate

that the King Vision™ VL has advantages compared to DL,

consistent with other VL performance in the current literature.

The King Vision™ was considered easier to use by participants,

had a higher success rate and better C-L scores. However, when

compared to other videolaryngoscopes, the King Vision™ VL is

less expensive, utilizes disposable blades, and is very portable.

The increased first pass success and C-L grade observed with

King Vision™ VL in this study are consistent with a 2014 study by

Murphy et al. using novice paramedic students in a cadaver model.

In this study, the King Vision™ VL had a higher success rate over

DL, faster time to intubation, and better C-L grades [10]. Although

our study showed insignificantly faster intubation times with DL

in the cadaver model, the time to intubate decreased by almost

50 percent with successive attempts using the King Vision™ VL,

indicating a rapid learning curve with the use of this device. In

the current investigation, both glottic opening visualization and

intubation success rates were significantly improved with the

King Vision™ VL using the cadaveric model. Two meta-analyses of

VL (GlideScope, X-Lite, Storz, McGrath, and Pentax-AWS) versus

DL found equivocal results in success rate, but a significantly

better view in difficult airways for VL. This is consistent with a

study by Murphy comparing King Vision™ to DL [6,10,11]. One

frequent finding is that increased visualization of the glottic

opening using VL may not proportionally translate to improved

success or faster intubation times [2,6,11,13,14]. DL failures are

typically due to inability to visualize glottic opening [14]. Most

failures with VL are not from poor visualization but instead, are

due to the inability to pass the ETT into the trachea [14-16]. This

is often due to incongruence between the location of the glottic

opening on VL and the trajectory of the ETT and is likely due to

advancing the VL blade too distally, positioning of the rigid stylet

used in the King Vision™ VL, or a very anteriorly placed glottis.

Subtle maneuvers, equipment modifications and practice can

reduce difficulties in passing the ETT. A Japanese meta-analysis

showed significant improvement in success and time to success

in VL (Airtraq and Pentax-AWS) with a channeled blade vs. DL

[9], facilitating placement of the tip of the endotracheal tube

much more anteriorly. The current investigation used a model

of the King Vision™ VL with the channeled blade. Although we

demonstrate a low failure rate consistent with most studies of

King Vision VL, the most common reason observed for a King

Vision™ VL intubation failure is poor technique, which can be

remedied using adequate training and briefly retraining if the

device is rarely used [17].

The King Vision™ VL may used as a teaching tool for

novice intubators similar to other VL, and has advantages over them for

training purposes due to its portable nature. Use of VL to train

novice intubators has shown higher success rates using DL for

endotracheal intubation in patients with normal airways as

compared to training utilizing DL [5]. The shortcomings of DL

for emergent intubators include significant training and practice

to become competent with the direct laryngoscope and poor

first-attempt tracheal intubation success rates [10]. The rapid

progression in time to intubation with the King Vision™ VL seen

in this data set is consistent with a study by Ayoub et al. which

demonstrated a more rapid acclimatization to VL with a drastic

decrease in time to intubation over 3 successive attempts when

compared to DL on surgical patients undergoing anesthesia

[5]. Several studies have demonstrated the ease of use of many

videolaryngoscopes with a shorter learning curve as compared

to DL [5,13]. In addition, any level user can easily gain skills in VL

because glottic visualization is not diminished to the same degree,

nor by the same factors that limit DL [4,18]. This is especially

pronounced in the difficult airway setting with VL success of

76.4% compared to DL of 8.8% in one study [4]. In addition to

steep learning curve and worse success with difficult airways,

another pitfall of DL is the deterioration of skills if not frequently

practiced. Murphy elaborates, ‘even in larger institutions and systems,

the opportunities to maintain intubation skill is limited,

with a significant proportion of practitioners having one or no

intubations per year’ [10]. Having a device that is easy to use and

portable makes continuing training easier to access and allows

the retention of intubation skills even in a setting of infrequent

intubation opportunities. Furthermore, it has been shown

that training on manikins is an adequate strategy if events to

train are rare or unpredictable [13]. Use of VL accelerates skill

acquisition, can be used as the primary training technique, and

can be used to retrain on manikins for infrequent practitioners

with sufficient quality in training.

The King Vision™ VL has several clinical advantages over

many other VL currently on the market in addition to ease of use

and portability. Two case reports discuss the King Vision™ VL

and its use clinically. One describes the success of King Vision™

VL for a difficult awake intubation of a patient with restricted

mouth opening in a remote area with limited resources [19]. The

King Vision™ VL was the only VL on the market that could have

successfully intubated this person as no other VL has as narrow

of a blade [19]. VL are also known for being easier to use than

fiberoptic intubating scopes in most patients as the approach to

intubating with VL is more similar to DL, the traditional method

used for intubating. The second case series used the King

Vision™ VL in awake intubations in patients with pathologic

abnormalities in airway anatomy making normal visualization

with standard DL impossible [17]. King Vision VL can be used

in the pre hospital environment. Studies with paramedics in a

simulated environment have shown King Vision™ VL is at least as good as and may be situationally more effective than DL under

unusual circumstances such as, entrapped patients with both

normal and difficult airways [10,20,21]. Other potential uses and

future studies include unexpected in-hospital code situations

on ward beds, international travel emergencies, public arenas,

disaster scenarios, and pre-hospital intubation.

There were several limitations to the current investigation.

The most obvious limitations were the small sample size and

the simulated environment in which this study was conducted.

In order to observe repeated measures data, ideally a repeat

study will be performed with sample size of significant power to

test the effects of different cadavers, the order in which the two

methods were applied, and all interactions to better determine

the factors that impact successful intubation. With the current

preliminary study, we do not have the sample size needed to

handle these more vigorous repeat measures analyses. We

believe with a more concrete selection process, we will likely

be able to confirm that, for most beginners, intubation using

the King Vision™ VL method will consistently demonstrate

improved C-L views, success rates, and time to intubation. The

King Vision™ VL is a relatively new device and as of the writing of

this article, a PubMed review did not identify any hospital based

clinical trials completed, although a large Swiss multicenter trial

protocol is written and currently ongoing with an objective of

comparing 6 VL, 3 channeled blades (King Vision™, Airtraq™, A.

P. Advance™)and 3 unchanneled blades (C-MAC™, GlideScope™,

McGrath™) in surgical intubation and an expected completion

date of August 2015 [22].

Conclusion

The King Vision™ VL not only improves visualization of the

glottic opening and intubation success rate, but it is easy to

use. Although intubation times were insignificantly longer with

the King Vision™ VL, cadavers were still successfully intubated

rapidly and students demonstrated drastic improvement with

successive intubations. Given the greater success rate of the King

Vision™ VL, the utility in intubating patients with a more difficult

airway most likely parallels other videolaryngoscopes. It is a

useful tool for training students and maintenance of intubating

skills. Considering the portable nature, low cost, ease of use, and

easy maintenance; the King Vision™ VL should be considered

to be an excellent videolaryngoscopic device in any emergent

setting where advanced airway management is required.

Acknowledgements

Ngosi, in memoriam.

Support

King Vision™ provided videolaryngoscopes and training

technicians for this study. All materials returned promptly at

end of study.

For more articles in Journal of Anesthesia

& Intensive Care Medicine please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/jaicm/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/jaicm/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment