Incidence and Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Among Critical Care Patients, Families, and Practitioners-Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Journal of Anesthesia

Abstract

OBackground: WAnxiety,

depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are common

complications of critical illness. Their prevalence is known to be

higher among patients than among the general population. Little is known

about their prevalence among families and among critical care staff.

Setting: Igeneral systems intensive care unit in a tertiary care university hospital

Methods: We measured the

features of PTSD, anxiety, and depression using validated scales

(PSS-SR, Zung anxiety scale, and PHQ-9 respectively), employing an

anonymous survey of sequential consenting patients admitted with

critical illness, their associated family next-of-kin (NOK), and members

of the clinical staff involved (medical, nursing, and allied health).

Survey was administered to patients and NOK at 28 days after ICU

discharge, and to staff at patient admission.

Results: 30 patients,

next-of-kin, and associated medical/nursing/allied health staff were

approached. Participants included 60%, 50%, and 58% of eligible

patients, NOK, and staff respectively. Among patients, NOK, and staff

respectively, features consistent with the diagnoses of PTSD (50%, 33%,

19%), anxiety (61%, 33%, 41%), and depression (39%, 20%, 16%) were

observed, substantially higher than expected based on population

prevalence estimates.

Background

A critical illness is a life-threatening event that

induces an intense response in its victim. Common, primordial responses

to imminent threats to life include fear and anger. Sadness, also a

basic emotion, intervenes concurrent with a sense of loss, whether acute

or chronic. Long term adverse sequelae after exposure to intense

life-threatening events include anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic

stress disorder (PTSD). Not surprisingly, these conditions occur more

frequently among critical care survivors than among the rest of the

population. Less is known about the incidence and prevalence of these

conditions among the families of critical care survivors and among

critical care practitioners [1-11].

Anxiety is characterized by excessive and usually

irrational concern about erstwhile non-threatening events or possible

events that is disruptive because it interferes with normal social or

economic function. It is distinguished from fear, a basic human emotion,

in that fear is directed at a realistic threat e.g. imminent death

during a critical illness. The life-time prevalence of anxiety in the

general population is approximately 10%. Generalized anxiety disorder is

described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV as including

three or more symptoms of restlessness, difficulty with sleep,

irritability, difficulty concentrating, or muscle tension in response to

normal stressors, and that interfere with usual function.

Depression similarly has a life-time population

prevalence of approximately 10%. As a major mood disorder, its

diagnostic features include significant variations in appetite, sleep,

concentration, and interactions with others, that interfere with usual

social and economic function.

PTSD is a mood disorder that is related to both depression

and anxiety, including features of each. The most distinct feature

of PTSD is its beginning with a traumatic event or series. Other

features include intrusive thoughts in relation to the traumatic

event that interfere with normal function, avoidance of scenarios

or places that may facilitate recall of the instigating event, and

biologic manifestations of a stress response such as sweating,

tachypnea, tachycardia, and flushing.

We sought to evaluate the incidence of anxiety, depression,

and PTSD among critical care survivors and their families, and

the prevalence of these among critical care practitioners. Our

objective was to determine whether these conditions occurred

at a different frequency compared to the non-critically ill

population and their families, and if so which of them was most

frequent.

Methods

The University of Alberta Hospital is a tertiary care centre,

within which the General Systems ICU (GSICU) includes 28 beds

for patients with medical, surgical, and traumatic critical illness.

After institutional approval, we conducted a survey of patients

(survivors), their families (immediate next-of-kin (NOK)), and

the providers involved in their care..

In June 2012, thirty consecutive unselected surviving ICU

patients and their NOK were approached and invited to provide

informed written consent for this investigation. Staff members

were invited to participate on the basis of providing care to

the participating patients at the time of their admission to the

ICU. Invited participating staff included the nurse, respiratory

therapist, resident, dietician, pharmacist, physiotherapist, and

attending staff for each patient. Staff members were limited to

participating once.

The survey was delivered to patients and their NOK at 28

days after ICU discharge, either using the standard postal

service if the patient had been discharged or transferred, or via

hand delivery if the patient remained in hospital. Surveys were

contained within a stamped self-addressed return envelope that

did not include personal identifiers. Surveys were delivered to

staff using hospital mail, using the same method of stamped selfaddressed

return envelope. The investigation was announced

and described to providers, who were advised of the study

methods. Provider consent was implied by survey completion,

and surveys did not include identifying information.

The survey consisted of three combined scales, and

nonidentifying

demographic descriptors. To assess the presence

of anxiety and depression, we used the Zung self-reported

anxiety scale and the patient depression questionnaire (PHQ-

9) respectively. PTSD was assessed using the post-traumatic

symptom scale (PSS-SR). Using the Zung scale, anxiety was

defined as a score of greater than 15. Depression was defined as

a score of greater than 15 on the PHQ-9. PTSD was defined as a score of

greater than 17 on the PSS-SR scale. Each of these scales

has been validated independently and shown to provide good

inter-rater and intra-rater reliability and validity [12-17].

Results

Of 30 patients and NOK approached, 18 patients (60%) and

15 NOK (50%) responded. Of ICU staff, 30 nurses, 5 respiratory

therapists, 2 dieticians, 2 physiotherapists, 2 pharmacists, 8

resident physicians and 6 attending physicians were invited to

participate. Responses were received from 20 nurses (67%), 3

respiratory therapists (60%), 6 resident physicians (75%), and

3 attending physicians (50%). No responses were received from

dieticians, physiotherapists, or pharmacists. The subsequent

results are based on the total of 65 responses received (overall

response rate 57%).

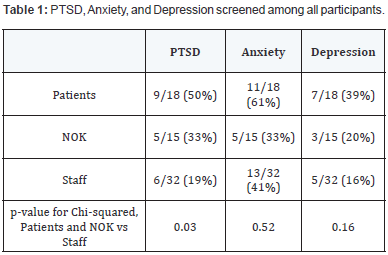

Considering Table 1, among patients participating after

surviving a critical illness, 50% met diagnostic criteria for PTSD

at 28 days after ICU discharge using the screening questionnaire

PSS-SR. This was also observed among 33% of the participating

NOK and among 19% of staff.

Also in Table 1, anxiety was present according to the Zung

scale among 61% of participating surviving patients and among

33% of the participating NOK. Anxiety was present among 41%

of critical care staff.

With regard to depression as measured by the PHQ-9, this

was present among 39% of participating surviving patients and

was present among 20% of their NOK. Depression was present

among 16% of participating staff.

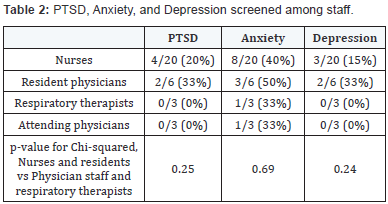

In Table 2, the presence of PTSD, anxiety, and depression

was considered among participating staff according to staff

category (e.g. nurse, physician, etc.). Symptoms of each of

PTSD, anxiety, and depression were more common among

participating nursing staff and resident physicians than among

participating respiratory therapists and attending physicians. It

was previously noted that none of the invited physiotherapists,

pharmacists, and dieticians participated in the survey, and no

conclusions can be drawn about these groups.

Discussion

The critical care unit in any hospital admits patients with the

greatest degree of physiologic disturbance and greatest threat

to life of patients in the hospital. The threat to life can leave

survivors and their NOK with persistent residual disturbances

in mood as a consequence of that threat. Constant exposure to

patients and NOK under threat to life may also be associated

with mood disturbance among bedside staff.

In this survey, we discovered that the prevalence of each of

PTSD, anxiety and depression were substantially higher among

patients, NOK, and staff than would have been expected based

on the general population prevalence of these conditions. While

detection of these mood disorders in ICU survivors and NOK

has been reported in the literature [1-11], this study represents

possibly one of the first that describes these conditions among

ICU staff. Further exploration of the causes and consequences of

these relatively increased incidences and prevalence, as well as

attention to prevention and treatment, may be appropriate.

Each of PTSD, anxiety, and depression are disorders that can

occupy a spectrum of implications on those with these conditions

ranging from mildly inconvenient to debilitating. Socially, their

recognition continues to carry varying levels of stigma that may

further reduce both their perceived prevalence and reported

significance. Consequently, the social burden of these conditions

may be substantially greater than measured in studies such as

this [12-13].

While we detected relatively increased prevalence of these

conditions among surviving patients and NOK, we were unable

to measure the duration of the conditions. Further investigation

to determine duration of these disorders would be appropriate.

We did not have the medical nor nursing resource to

address the effectiveness of possible preventive or therapeutic

manoeuvres. While we did advise participants to contact their

family physicians in event of concerns, we did not wish to

raise expectation bias in survey completion by emphasizing

therapeutic options.

The therapies available for these conditions range from

cognitive behavioural therapy to pharmaceutical. In the most

severe scenarios, patients may be treatment-resistant and debilitated. Consequently, identification of preventive strategies

may be beneficial [12-18].

The higher prevalence of these disorders among nursing

staff and resident physicians is somewhat in keeping with

other findings in the literature showing higher prevalence

of such conditions among first-responders to critical events.

First-responders have less ability to remove themselves from

exposure to events that are life-threatening to patients, and may

suffer from internalization of this exposure. On the other hand,

attending staff and associated staff (e.g. pharmacists, dieticians)

may be unaware of the significance of the perceived threats to

life on bedside providers. A greater level of awareness of this

may be appropriate for both first-responders and for those more

removed from the moment-to-moment intensity.

This study was too small to evaluate association between

severity of patient illness and its effect on immediate NOK or

on immediate care givers. Further investigation could evaluate

these hypotheses.

Considering the prevalence of these conditions among

patients, it is noted that this was a sequential (cross-sectional)

non-randomized survey that was done at 28 days after ICU

discharge and was obviously limited to survivors. Administration

of this survey later after discharge may have resulted in a

different detected prevalence of these conditions. However, due

to timing constraints, we were not able to include patients that

were admitted during the study period and survived but that

remained within the ICU due to severity of illness. These patients

would likely have been exposed to greater threat, as would

also have been the case for their NOK. A randomized design

performed over a longer period of time may have achieved

a different result, as the conclusions of this study may have

been affected by timing of administration. Finally, the response

rate (60%) among patients was reasonable to allow some

generalization to the surviving non-responding patients. The

response rate among NOK was slightly lower, and was limited

to study of NOK of surviving patients. Interestingly, the response

rate among staff was similar to that among patients, and is also

probably appropriate for some generalization.

Within these limitations, the incidences of PTSD, anxiety,

and depression were higher among patients and NOK, as well

as among staff, than expected among the population at large.

Consideration of further investigation to determine causes

of these conditions in these groups, as well as to evaluate

prevention, treatment, and long-term sequelae, would be

appropriate.

For more articles in Journal of Anesthesia

& Intensive Care Medicine please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/jaicm/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/jaicm/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment